Climate Equality Litigation and Transformative Justice

Monica Visalam Iyer

Perhaps the most optimistic view of the climate crisis is that it presents an opportunity, or even a necessity, to forge a new vision of the world that we share. If we are to face the threat of global warming, this must be done not only in a manner that is environmentally sustainable, but also in a way that reckons with historical and structural inequalities and provides opportunities for all people, as well as nature, to thrive. However, while climate litigation may provide an important tool for addressing some of the disproportionate impacts that climate change has on historically marginalized groups or individuals, there is significant skepticism about the power of such litigation to effect transformative or systemic change. This essay provides a brief overview of the advocacy that calls for a just transition that represents a break with past systems and structures of inequality and examines why litigation has been thought inadequate to contribute to that change. Then, calling on climate litigation databases, it examines the remedies sought and granted in climate cases brought under equal protection laws to determine whether, and if so how, any such cases have offered the possibility of addressing historic or structural inequalities. Finally, drawing on the literature of reparative and transformative justice, it will explore whether there are avenues through which climate litigants might be able to seek more transformative outcomes. Ultimately, the essay argues that well-crafted remedy requests and carefully considered litigation strategies can enable climate equality litigation to drive transformative justice.

Table of Contents

I. A New World from the Ashes? Climate Change as Opportunity for Transformation 290

II. The (Im)Possibility of Transformational Change Through Litigation 295

III. Climate Equality Litigation Efforts thus Far 299

IV. Possibilities for the Future 305

From many places around the world, and especially from the United States, the climate future in 2025 looks bleak. Record summer heat pummeled people from Pakistan[1] to Punxsutawney.[2] Climate scientists have warned that global average temperatures will soon warm beyond the target set in the Paris Agreement[3] and that a range of climate tipping points are imminent.[4] The Trump Administration has withdrawn from the Paris Agreement and has sought a significant rollback of domestic climate action.[5] A coalition of more than 200 civil society organizations has proclaimed that global climate negotiations are at a breaking point and “increasingly perceived as out of touch, driven by vested interests, and running out of relevance and trust.”[6] And as climate harms grow, so too does inequality. It is widely understood and acknowledged that climate change’s worst impacts will fall on individuals and groups who have already been the targets of historical discrimination and marginalization,[7] and that income and other gaps between these groups and the general population will be exacerbated by these impacts.[8]

Despite all of this bad news, however, there are points of light. In particular, in advisory rulings handed down in the summer of 2025, both the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (responding to a request from Chile and Colombia)[9] and the International Court of Justice (as requested by a unanimous resolution of the General Assembly)[10] examined the questions of States’ legal obligations to take climate action and affirmed that international law, including international human rights law, imposes significant obligations in this regard. There are also people who refuse to give up hope that better climate outcomes are possible and who seek to turn “fear into action.”[11] Many of these advocates argue that as climate change presents the necessity of transformational change, it also provides an opportunity to pursue transformations beyond energy use or consumption habits and to address systems of inequality and injustice.[12] But where will these kinds of transformations come from? With climate negotiations alleged to have “systematically failed to deliver climate justice”[13] and domestic political leaders largely unwilling to stray too far from the interests of wealthy and powerful fossil fuel constituencies,[14] many are turning to litigation as a last best hope for stirring climate action. At the same time, however, litigation is widely acknowledged to be an inadequate tool for achieving systemic change.[15] Is this correct? Is there any way that climate litigation can also seek to address systemic inequalities?

This essay examines a subset of climate litigation—that which already operates at the intersection of climate change harms and systemic inequalities by raising claims under equal protection laws—in order to evaluate the extent to which the remedies sought in such cases have the potential to address systemic underlying causes. In doing so, it analyzes the potential for such litigation to achieve, or contribute to the achievement of, what I refer to as transformative justice: a legal result designed to address past inequality and promote systemic change. I argue that ultimately, through carefully crafted remedy requests and broader litigation and advocacy strategies, climate equality litigation can be a vehicle of transformative justice. Part I of the essay describes calls for a climate transition that tackles inequality. Part II explores why litigation has largely been seen as unable to meaningfully contribute to such calls. Part III draws on climate litigation databases to identify “climate equality” cases and the remedies sought in such cases. Finally, Part IV concludes with some reflections, drawing in particular on reparations literature, on how climate equality litigation might contribute to transformative change.

I. A New World from the Ashes? Climate Change as Opportunity for Transformation

A number of climate change advocates now insist that climate change presents both an opportunity and a necessity for fundamental global social and economic transformation.[16] Responding to this emergency provides a chance to abandon exploitative and unequal economic and social models, which have been predicated on hierarchies of human value and commodification of nature, in favor of more just and cooperative societies that stay within planetary boundaries.[17] One of the most prominent of these advocates is Naomi Klein, who says in the introduction to her seminal climate book, This Changes Everything, that “climate change . . . could become a galvanizing force for humanity, leaving us all not just safer from extreme weather, but with societies that are safer and fairer in all kinds of ways as well.”[18] These arguments form part of the just transition discourse that calls for greater attention to workers and those who will potentially be most negatively affected in the movement away from fossil fuels,[19] but such arguments may also involve broader and more systemic transformation.[20]

Much of this discourse is focused on economic systems, as reflected, for example, in the subtitle to Klein’s book: “Capitalism vs. The Climate.” Advocates focus on the current exploitative model of global capitalism as being unsustainable. Some have called for a “de-growth” model[21] or a “doughnut economy,” which uses enough resources to ensure humans and ecosystems can thrive, but not so much that we exceed what the planet can handle.[22] But as the quote from Klein above makes clear, many advocates are also thinking beyond economic inequalities to climate change as being a chance to address other systemic inequalities that have historically been built on discrimination and prejudice against marginalized groups.[23] As Rebecca Bratspies phrases it, the “[k]ey to a just transition, as opposed merely to a transition, is the involvement of those most affected by the changes, and the intentional disruption of structural inequalities embedded in pre-existing economic and environmental policies.”[24]

In the understanding of these thinkers and advocates, as elaborated below, addressing inequalities based on race, ethnicity, indigeneity, gender, age, disability status, sexual orientation, gender identity, and other factors is a necessary part of climate action. These inequalities are so inextricably intertwined with the economic system that perpetuates the climate crisis that we cannot address one without addressing the other. Failing to address these inequities will lead to a failure of climate action. Essentially, there is no way to construct a system that ends the unsustainable commodification and exploitation of the earth while continuing unsustainable commodification and exploitation of humans.[25] Failing to address these inequalities will also mean a failure to comply with existing human rights obligations for many countries, as multiple international courts have found that States have obligations to take climate action in a manner that takes into account intersectional inequalities.[26] Further, the global scale of the problem of climate change is such that everyone needs to be empowered to take climate action, and addressing systemic inequalities is a means of bringing everyone into solutions.[27] It is also a means of ensuring that there is no backlash against climate action that may be seen as privileging the concerns of elites. Transformative climate action that addresses systemic inequalities can enjoy broad popular support, while climate action that only addresses the concerns of those who already enjoy power will face popular resentment.[28] Relatedly, historically marginalized groups may offer new ways of thinking about climate problems and new adaptation tools and techniques; perpetuating systems of marginalization and discrimination forecloses our access to those solutions.[29] Klein documents, for example, how Indigenous opposition to fossil fuel exploitation created a new sense of mobilization and possibilities for coalition building in Canada and “sparked a national discussion about the duty to respect First Nation Legal Rights.”[30] This movement opened up possibilities for reevaluation of the relationship between Indigenous communities and settler-colonial states and new opportunities for addressing historical wrongs in the treatment of these communities.[31]

Legal scholars have taken up analysis of calls for a just transition, debating which conceptions of justice are or should be at the heart of such calls.[32] Love Alfred, for example, uses a Third World Approaches to International Law (TWAIL) lens to argue that “a just transition for developing nations will involve a restorative and whole [energy transition] policy framework that seeks to minimise or reverse culminative impacts of energy systems at local levels, including negative impacts on communities disproportionately burdened by energy production, distribution and consumption.”[33] He elaborates that “a transition that leaves socioeconomic inequalities intact, will not deliver a result that is ‘sustainable.’”[34] Highlighting the potential risks of different movements and legal theories offering different visions of a just transition, Elizabeth J. Kennedy argues that “[a]n integrative framework can resolve competing justice narratives, but it must prioritize racial equity and worker power to avoid replacing one form of climate apartheid with another.”[35] The United Nations Secretary-General has also linked just transition and climate justice, noting the necessity of “redress for environmental injustices and historical discrimination.”[36] All of these proposals suggest that law at the international, domestic, and local levels can contribute to crafting just transition solutions that also seek to address historic inequalities by structuring frameworks of action and remedy.[37] However, the ability of litigation to contribute to these kinds of solutions seems less apparent. The next section explores the ways in which litigation has been weighed, measured, and found wanting for these purposes.

II. The (Im)Possibility of Transformational Change Through Litigation

Climate change is a global, multi-causal phenomenon,[38] and its harms are inextricably linked with other global, multi-causal phenomena,[39] including systemic disparities.[40] This means that society-wide transformation, as envisioned by just transition advocates, is necessary to address climate change. As Maxine Burkett has highlighted, “[t]he vast majority of claims in the US, however, have not broached the special needs of the climate vulnerable. Claims on behalf of the climate vulnerable . . . are far less frequent, and the plausibility of their success is even more remote.”[41] As described in this Part, a wide range of scholars have expressed the view that this sort of “wicked problem”[42] is beyond what litigation is capable of handling. As Pablo de Grieff argues, “the norms of the typical legal system are not devised” to address “violations that, far from being infrequent and exceptional, are massive and systematic.”[43] Some of the failings of litigation highlighted in these types of cases are procedural, while others are more substantive.

On the procedural side, there are significant resource constraints on courts that bar them from taking on every case of every individual subject to a mass harm.[44] There are also concerns that allowing multiple courts to address individual cases resulting from mass harm will lead to inconsistent results rather than a holistic solution.[45] Scholars have also suggested that common litigation hurdles, “such as the statute of limitations, justiciability and causation” tend to do more to prevent access to justice than to achieve remedy for harms in these cases.[46] Indeed, a number of courts have found themselves barred from considering climate cases as a result of standing or political question doctrines.[47]

Substantively, advocates and scholars question the possibility that litigation can lead to a deep reckoning with structural harms[48] and emphasize that courts generally tend to operate in the service of powerful actors and preserve the status quo of power and economic distribution through either ruling against disadvantaged parties or closing the courthouse doors to them.[49] Beyond failing to achieve adequate remedies for harms, litigation can at times actually inflict new harms of its own, including through stressors on litigants and the possibility of making bad law or generating backlash.[50]

Given all of these valid concerns about the capability of litigation to meaningfully address climate harms, especially when they are interrelated with systemic discrimination, it might be expected that advocates and affected communities would abandon litigation altogether to focus on political and policy solutions. But, as Burkett points out, “political processes are yielding little by way of substantive action or long-term reconciliation or repair,”[51] leading to condemnations of climate negotiations as “increasingly perceived as out of touch, driven by vested interests, and running out of relevance and trust.”[52] Perhaps because of this, climate litigation continues to grow, including the subset of climate litigation that relies on laws designed to address historical inequalities, which we may term “climate equality litigation.” The following section examines a number of these cases to determine whether, while addressing climate harms, they have also sought to remedy the systemic discrimination that may underlie or magnify those harms.

III. Climate Equality Litigation Efforts thus Far

Using the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law’s United States and global Climate Change Litigation Databases[53] and the NYU Law Climate Law Accelerator’s Climate Rights Litigation Database,[54] it was possible to evaluate the kinds of relief sought in climate equality litigation and its potential for transformative change. From these databases, there are thirty-four identifiable cases in domestic and international courts and tribunals where claims were brought under equality or anti-discrimination statutes or treaties seeking to address harms to historically marginalized individuals or communities.[55] This does not include cases contained in these databases concerning such individuals or communities that did not rely on equality or anti-discrimination statutes and/or cases that used equal protection statutes but did not address the concerns of those who have historically been subject to discrimination.

Of the thirty-four cases reviewed, thirty were brought using general anti-discrimination or equal protection laws, such as Juliana v. United States, which incorporated Fifth Amendment equal protection claims,[56] and R v. Secretary of State for Business Energy and Industrial Strategy, which brought claims under the United Kingdom’s Equality Act 2010.[57] Three involved statutes offering specific protection for the rights of Indigenous Peoples, including under Brazilian[58] and Korean law.[59] Two involved gender equality laws in Pakistan[60] and Ireland,[61] and one included a claim under laws protecting the rights of future generations.[62] (As is evident from some simple mathematics, some of these cases invoked multiple equal protection statutes.) Among the types of plaintiffs represented, children, youth, and future generations were far and away the most common, appearing in twenty cases.[63] Historically economically marginalized communities[64] constituted the plaintiff group in six cases. Indigenous Peoples were the plaintiffs in four cases,[65] women in three,[66] and persons with disabilities in two.[67] From these statistics, it is worth noting that some seemingly viable bases for climate equality litigation, like race, gender, and disability discrimination laws, might currently be under-utilized. While these types of statutes are prevalent in many countries and people protected by these statutes face disproportionate climate impacts, there have been very few cases brought under these statutes thus far. Finally, as of July 2025, eleven of the cases included were still pending. Fourteen had resulted in final outcomes in favor of the defendants, and nine had resulted in final outcomes in favor of the plaintiffs.

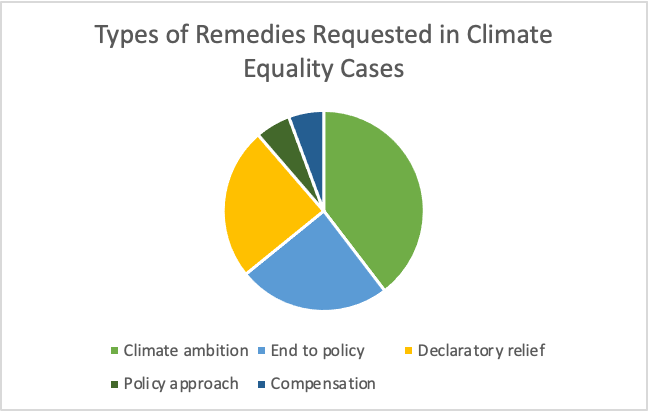

After canvassing this basic information about the identified cases, I focused in particular on the remedies sought. As with the types of statutes relied on, several cases sought multiple remedies. The most common type of relief sought was more ambitious climate or environmental policies, which were the goal of twenty-one cases. This represents a very common type of climate rights litigation, which argues that insufficiently strong climate action leads to rights violations.[68] For example, the Friends of the Irish Environment case challenged Ireland’s national climate mitigation plan for not including sufficient short-term targets, arguing that this failure violated both climate laws and human rights law, including the guarantee of equal protection of men and women.[69] The remedy request was for a new climate plan that would include more ambitious short term mitigation targets but did not include any measures designed to address the identified disparities between men and women. The next most common remedy requests were for the termination of a specific project or policy that was leading to climate harms or for declaratory relief, including declarations of a breach of duty or a violation of human rights law, or recognition of rights, like the right to a healthy environment. These forms of relief were each sought in thirteen cases. An example of a case seeking the end to a specific plan or policy is the Mina Guaíba Project case in Brazil, which challenged the approval of an open-pit coal mining project.[70] This case showed more concern for systemic discrimination issues as it sought better consultation with Indigenous communities before approval of this kind of project. Another prominent case seeking declaratory relief is the La Rose case in Canada, which asked for a number of declarations recognizing human rights and equal protection violations.[71] Although declaratory relief can be understood as only providing rhetorical support for these positions, it does provide an important foundation to build towards greater recognition of human rights, including acknowledgment of systemic discrimination. Three cases requested implementation of a specific approach to law-making, including ensuring free prior and informed consent of affected Indigenous Peoples, a best interest of the child standard, or consultation with affected communities, as in the Mina Guaíba Project case referenced above. Finally, three cases requested compensation or monetary reparations, including compensation for past harm, climate finance, or a symbolic compensation order. For example, the ENVironnement JEUnesse v. Procureur General du Canada case asked for compensation of 100 CAD for each plaintiff.[72] This amount would make little financial difference for either the plaintiffs or the State but provides important recognition of the remedy and reparation due to structurally marginalized communities that are disproportionately impacted by climate change. The chart below provides a visual representation of these results.

This typology of remedies in climate equality cases invites certain takeaways. First, it seems clear that most cases are either focused on specific harmful policies or are more broadly seeking more ambitious climate action. These types of efforts are important, but they do not necessarily address the systemic discrimination that ensures that climate harms fall disproportionately on certain individuals and communities. At times, these remedies could seek to address systemic harms, as in the Mina Guaíba Project case, where the relief sought included better consultation with Indigenous communities. One could also imagine a request for a more ambitious climate mitigation plan that also requested that that plan include special measures for marginalized communities, but that does not seem to have occurred in climate equality litigation thus far.

Other commonly sought remedies have more potential, however. Litigants in climate equality cases have often sought declaratory relief, which can advance legal interpretation in ways that simultaneously address climate harms and systemic discrimination. Declaratory relief can also influence public opinion and stakeholder interpretation of these issues. As noted above, the rhetorical nature of declaratory relief may be frustrating for litigants and advocates seeking to bend the moral arc of the universe more quickly and sharply towards justice. But this kind of relief can result in authoritative statements regarding law that lays the groundwork for future litigation, as in the Advisory Opinions recently issued by two international courts.[73] It can acknowledge important and expansive legal evolution, such as recognition of the right to a healthy environment, that can then be used in substantive cases.[74] Furthermore, like symbolic compensation, it can fill an important signaling function for marginalized communities, recognizing that their struggle has not been in vain and acknowledging the harms they have experienced.

Calls for the application of specific frames in policy-making, through continued normalization of free, prior, and informed consent, best interest of the child, or community consultation, also help to advance systemic justice by ensuring that the voices and the preferred solutions of those most affected are included in policy-making. One key aspect of structural discrimination and inequality is that Indigenous Peoples, children and youth, and marginalized communities are systematically excluded from spaces where decisions about their lands and lives are made, including climate and environmental policy spaces. Structured consultation and participation frameworks help to remedy this wrong and allow for future decisions to be made with the input, and ideally the leadership, of those most affected.[75]

Finally, while compensation is generally understood as narrow and ill-suited to systemic change, compensation requests can be framed in a manner that then goes beyond damages to individuals, including requesting symbolic compensation (like the 100 CAD/claimant in the ENVironnement JEUnesse case) or demanding compensation sufficient to repair social and environmental harms. In this way, compensation requests in climate equality litigation can form part of broader calls for climate reparations that recognize the links between climate change loss and damage and other systemic harms.[76] Overall, these findings suggest that while most climate equality litigation thus far does not seek to bring about transformational change related to underlying systemic discrimination, there are still circumstances under which such cases can contribute to this kind of change.

IV. Possibilities for the Future

As noted above, despite all of the practical and structural ways that litigation might be ill-suited to address a problem as widespread and complex as climate change, those seeking climate action have not given up on litigation. To the contrary, there is a recognition that, “[a]s the impacts of climate change become increasingly severe, divisive legal claims might be the best of many far less coordinated alternatives.”[77] Indeed, there is increasing attention to “strategic” climate litigation that seeks “to produce ambitious and systemic outcomes.”[78] For human rights advocates, including those seeking to address the intersection of climate harms and systemic discrimination, there is a recognition that “strategic human rights litigation can also catalyse and contribute to much broader changes, of a legal, political, institutional, social or cultural nature.”[79]

Litigation has been acknowledged as an important contributor in seeking justice in situations in need of repair. Reparations scholar Eric Yamamoto argues that litigation provides an important site for formal recognition of reparations claims[80] and that “when reparations claims are reframed within the law-based paradigm and beyond it in terms of moral, ethical and political dimensions of ‘repair,’ reparations can address both the improvement of present-day living conditions of a historically oppressed group and the healing of breaches in the larger social polity.”[81] This has important applications for climate change, a situation where there are clearly both ongoing impacts on historically oppressed groups and deep breaches in the larger social polity. It is for this reason that an environmental lawyer like Abigail Dillen can point to continued faith in “the power of law . . . as we work to repair that irreparable damage and rise to the awesome challenges that face us now.”[82] Importantly, in this manner, litigation can contribute to societal change whether it is “successful” in terms of achieving a favorable ruling or not.[83] Paul Rink has documented how cases like Juliana, a climate case brought by youth plaintiffs in the United States, while not “winning” in court, have “elevated the salience of issues, garnering prominent attention,”[84] “provid[ed] a bulwark against climate disinformation,”[85] and “support[ed] further legal advocacy.”[86] They also point to how one of the first attempts at climate human rights litigation, an effort by Inuit activists to bring a petition before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, while being rejected by the Commission, “motivated a coalition of leaders from Small Island Developing States to develop the Malé Declaration on the Human Dimension of Climate Change, which became the first international agreement to explicitly state that climate change threatens the full enjoyment of human rights.”[87] The broader conversation sparked by litigation may ultimately shift public opinion or outcomes outside of the four corners of the case at hand.

Remedy requests form an important part of the contribution that litigation makes to change. In climate cases, study is beginning to reveal that while remedies are not determinative of outcomes or long-term impact, they do play a role in how cases are decided and how implementation plays out. For example, Juan Auz has found that a number of factors go into compliance with remedies in Latin American climate cases, including “financial, political, social, and administrative burdens” on the State in question.[88] Camila Bustos argues that while “the type and scale of remedy ordered” make a difference for compliance and implementation in climate cases, “institutional capacity and strength,” “the court’s ability to retain supervisory authority,” and “the role of coalitions and stakeholders in raising the costs of non-compliance” all also play a role.[89] How then, can litigants in climate equality cases ask for remedies that seek repair? Burkett suggests that such remedies should be ones “that are justified by past harms and are also designed to assess and correct the harm and improve the lives of the victims into the future.”[90] In order to do this, they “must introduce mechanisms that limit the ability of the perpetrator to repeat the offending act”[91] and have the goal of “correcting the present-day effects of past wrongs, effectively shifting from redress to address.”[92] De Grieff suggests that justice in a reparations program consists of achieving the goals of recognition, civic trust, and social solidarity;[93] furtherance of these goals might also be sought through remedies in climate equality litigation. Duffy has noted that strategic human rights litigation can lead to changed legislation or better enforcement of existing legislation,[94] as well as changes to policies or practices,[95] and “increasingly creative use of remedies is becoming an important tool for trying to bring about . . . strategic goals” through human rights litigation.[96] In the climate litigation space specifically, Juan Auz and Marcela Zúñiga identify a number of “emerging best practices” for remedies, including ensuring effective redress, crafting remedies that are holistic, and adhering to standards of care.[97]

Drawing on these scholars and on the trends already seen in remedy requests in climate equality litigation, we can develop some suggestions for the kinds of demands for relief that could be made in this type of litigation going forward. Climate litigation is more successful when its remedy requests are specific,[98] and remedies that are more affordable and feasible are more likely to be met with compliance.[99] However, specific requests can be crafted with the possibility to contribute to or effect broad change, and while ultimately systemic transformation will entail monetary costs, modest requests can make contributions to systemic efforts. In order to ensure that remedy requests are both specific and feasible, litigants should consider both the content of remedies and the details of form and implementation.[100] In asking governments to implement more ambitious climate policies, for example, litigants can also ask that such policies be designed to take into account historic disparities and can draw on the already established practice of requesting that policy-makers consult meaningfully with affected communities and employ standards like free, prior, and informed consent and best interest of the child. Declaratory relief requests can be crafted to include acknowledgement of the historical inequities associated with climate harms or to recognize the human rights imperative to consider systemic and intersectional patterns of discrimination and inequality when implementing environmental and climate laws. Compensation demands, whether substantial or symbolic, can be explicitly framed as reparations and distributed in a manner that takes into account past discrimination.

Beyond remedy requests, climate equality litigation’s potential to contribute to transformative changes depends in part on its being conceived as a component of a broader strategy. In addition to obtaining specific transformative remedies, there is also the possibility that litigation might galvanize broader change. For example, Yamamoto traces how litigation around World War II era Japanese internment in the United States helped to spur legislative action on reparations.[101] He suggests that, as well as carefully crafting remedies in particular cases, we should consider “law and court process—regardless of formal legal outcome—as generators of ‘cultural-performances’ and as vehicles for providing outsiders an institutional public forum.”[102] Litigation can form a site and a catalyst for creative coalition-building and innovation of legal and advocacy strategies.[103] It can also generate social and psychological benefits for historically marginalized communities: “The affirmation or denial of identities through court cases and litigation-linked advocacy activity can have profound impacts on whether litigation is a tool of empowerment or oppression for litigants and associated grassroots communities.”[104] In order to capture such benefits, “litigation must be developed and conducted as one part of a broader plan for how advocates will achieve the desired change.”[105] Climate equality litigants and their attorneys should undertake “a rigorous assessment of each case that goes beyond the chances of winning the case on its own terms.”[106] They should also undertake to understand the risks that litigation might pose to broader goals and work with advocates to address or mitigate those risks.[107]

Humanity’s history may be dark with injustice and inequity, and our planet’s future may look bleak. But all hope is not lost. A great deal of work is needed in many different spheres of human activity to enable a genuine transition to a sustainable, thriving planet and a just economic, social, and political model. Through well-crafted remedy requests and careful broader strategy, climate equality litigation can contribute to that transition.

-

E.g., Arsalan Khattak, June 2025 Becomes Hottest Month on Record in Pakistan, ProPakistani (July 8, 2025), https://propakistani.pk/2025/07/08/june-2025-becomes-hottest-month-on-record-in-pakistan/#:~:text=The%20extreme%20heat%20affected%20nearly,to%20June%20period%20ever%20recorded [https://perma.cc/E2GN-Z7FY] (“Pakistan experienced its hottest June ever in 2025, with temperatures breaking previous records across the country.”). ↑

-

See Emily Shapiro & Kyle David, Record-Shattering Heat Wave Hitting Wide Swath of US: Latest Forecast, ABC News (June 20, 2025), https://abcnews.go.com/US/record-shattering-heat-wave-hitting-wide-swath-us/story?id=123035114 [https://perma.cc/62KG-4497] (noting that “[d]aily record highs are possible from Detroit to Raleigh, North Carolina, to Boston”); Greg Williams, First Heat Wave of 2025 Is Here, The Sentinel (June 23, 2025), https://www.lewistownsentinel.com/news/local-news/2025/06/first-heat-wave-of-2025-is-here [https://perma.cc/B9JW-656H] (“The Juniata Valley and much of central Pennsylvania is experiencing a significant and dangerous heat wave, which began Sunday, with temperatures climbing into the 90s and heat index values potentially reaching dangerous levels, prompting an Extreme Heat Watch for multiple counties.”). ↑

-

See Damian Carrington, Only Two Years Left to Limit Global Warming to 1.5 Degrees Target, Scientists Warn, Irish Times (June 19, 2025), https://www.irishtimes.com/environment/climate-crisis/2025/06/19/only-two-years-left-to-limit-global-warming-to-15-degrees-target-scientists-warn [https://perma.cc/Y7B4-LB8R] (“The planet’s remaining carbon budget to meet the international target of 1.5 degrees has just two years left at the current rate of emissions, scientists have warned, showing how deep into the climate crisis the world has fallen.”). ↑

-

See generally David I. Armstrong McKay et al., Exceeding 1.5°C Global Warming Could Trigger Multiple Climate Tipping Points, 377 Sci. 1171 (2021) (identifying key global and regional tipping points and arguing that multiple are likely to be triggered). ↑

-

See Climate Backtracker, Sabin Ctr. Climate Change L., https://climate.law.columbia.edu/content/climate-backtracker [https://perma.cc/79AH-B7EQ] (last visited July 7, 2025) (identifying actions “taken by the Trump-Vance administration to scale back or wholly eliminate federal climate mitigation and adaptation measures”). ↑

-

Climate Acton Network et al., Reclaiming Climate Justice: An Urgent Call for Reform of the UN Climate Talks 1 (2025). ↑

-

See, e.g., U.N. Secretary-General, The Impacts of Climate Change on the Human Rights of People in Vulnerable Situations, ¶ 4, U.N. Doc. A/HRC/50/57 (May 6, 2022) (noting that those who may be “disproportionately at risk from the adverse effects of climate change” include “indigenous peoples, local communities, peasants, migrants, children, women, persons with disabilities, people living in small island developing States and least developed countries, persons living in conditions of water scarcity, desertification, land degradation and drought, and others in vulnerable situations who are at risk of being left behind”). ↑

-

See, e.g., Renee Zahnow et al., Climate Change Inequalities: A Systemic Review of Disparities in Access to Mitigation and Adaptation Measures, 165 Env. Sci. & Pol’y, no. 104021, 2025 at 1, 1 (“[Those] most vulnerable to the effects of climate change . . . have the poorest access to and capacity for participation in adaptation and mitigation initiatives. They will also be the most disproportionately affected by government policies such as taxation on fuel and compulsory requirements for energy-efficient devices.”). ↑

-

See Climate Emergency and Human Rights, Advisory Opinion AO-32/25, Inter-Am. Ct. H.R. (ser. A) No. 32, ¶ 291 (May 29, 2025) (“The existential interests of all individuals and species of all kinds . . . whose rights to life, personal integrity, and health have already been recognized by international law, crystallize the obligation to abandon anthropogenic conducts that pose a critical threat to the equilibrium of our planetary ecosystem.”). ↑

-

See Obligations of States in Respect of Climate Change, Advisory Opinion, ¶¶ 112–404 (July 23, 2025), https://www.icj-cij.org/sites/default/files/case-related/187/187-20250723-adv-01-00-en.pdf [https://perma.cc/Q7K5-9UDV] [hereinafter Obligations of States] (identifying and clarifying the obligations of states under relevant international law); Karen Zraick & Marlise Simons, Top U.N. Court Says Countries Must Act on Climate Change, N.Y. Times (July 23, 2025), https://www.nytimes.com/2025/07/23/climate/icj-hague-climate-change.html (on file with the Columbia Human Rights Law Review) (“The International Court of Justice issued a strongly worded opinion on Wednesday saying that states must protect people from the “urgent and existential threat” of climate change, a major moment for the global environmental movement and for the countries at greatest risk of harm.”). ↑

-

E.g., Jonathan Watts, ‘This is a Fight for Life:’ Climate Expert on Tipping Points, Doomerism, and Using Wealth as a Shield, Guardian (June 24, 2025), https://www.theguardian.com/environment/ng-interactive/2025/jun/24/tipping-points-climate-crisis-expert-doomerism-wealth [https://perma.cc/7UPW-5MHU] (providing Dr. Genevieve Guenther’s approach to assuaging fears around climate change by cultivating collective action). ↑

-

See infra Part I (describing calls for a climate transition that tackles inequality). ↑

-

Climate Acton Network et al., supra note 6, at 1. ↑

-

See Zoë Schlanger, Environmental Internationalism is in Its Flop Era, Atlantic (Dec. 13, 2024), https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2024/12/environmental-diplomacy-had-a-terrible-year/680983 [https://perma.cc/64BD-SAFQ] (describing wealthy countries unwillingness to commit to climate action and the influence of fossil fuel industry concerns in climate negotiations). ↑

-

See infra Part II (exploring why litigation has largely been seen as unable to meaningfully contribute to calls for a climate transition that tackles inequality). ↑

-

E.g., Kate Aronoff et al., A Planet to Win: Why We Need a Green New Deal 17–27 (2019) (discussing the need for radical social and economic change in response to the climate crisis); Ann Pettifor, The Case for the Green New Deal 31 (2020) (“[I]f we are to fulfil the goal of a fundamental, system-wide transformation of the economy to save the ecosystem, then we must combine and cooperate at an international level to bring about a revolution in the power relations of the globalised and dollarized economic system.”); Carola Rackete, The Time to Act is Now 118 (2021) (“We have to transform every part of our existence; not just the structure of our states, but our very way of life.”). ↑

-

E.g., Aronoff et al., supra note 16, at 17–27 (discussing the need for radical social and economic change in response to the climate crisis); Pettifor, supra note 16, at 31 (“[I]f we are to fulfil the goal of a fundamental, system-wide transformation of the economy to save the ecosystem, then we must combine and cooperate at an international level to bring about a revolution in the power relations of the globalised and dollarized economic system.”); Rackete, supra note 16, at 118 (“We have to transform every part of our existence; not just the structure of our states, but our very way of life.”). ↑

-

Naomi Klein, This Changes Everything 6 (2014). ↑

-

E.g., Gillian K. Joyce, Left in the Dust: The Decline in Coal Mining and the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act’s Failure to Incorporate Just Transition Principles for Coal, 41 Hofstra Lab. & Emp. L. J. 173, 185 (2023) (“In a [just transition], the shift to greener economies should not cost workers or communities their ‘health, environment, jobs, or economic assets.’”). ↑

-

See, e.g., Adebayo Majekolagbe, Just Transition as Wellbeing: A Capability Approach Framing, 14 Ariz. J, Env’l L. & Pol’y 41, 42–43, 68–69 (2003) (offering “key characteristics of what should be considered just in the context of climate change-focused sustainability transition,” including an objective to “ensur[e] that existing injustices to environment, culture, and people are redressed and that sustainability initiatives do not reinvent previous injustices.”); Love Alfred, A Just Energy Transition Through the Lens of Third World Approaches to International Law, 21 Opole Stud. Admin. L. 9, 11 (2023) (noting that on a global scale, “the goal of global decarbonisation is likely to be unsuccessful if the problem of equity and inclusion for developing countries is not addressed”); Rebecca Bratspies, What Makes it a Just Transition? A Case Study of Renewable Rikers, 40 Pace Envt’l L. Rev. 1, 6 (2022) (“At its broadest, the term ‘just transition’ has been defined as moving from an extractive economy to a regenerative economy in a fashion that is just and equitable. That means not only redressing past harms, but also building new power structures and economic relationships moving forward.”); J. Mijin Cha et al., Environmental Justice, Just Transition, and a Low-Carbon Future for California, 50 Envt’l L. Rep. 10216, 10217 (2020) (“However, a truly just transition must go beyond the impact on fossil fuel workers and communities and address the disproportionate environmental burden that fossil fuel extraction and use has had on communities of color and low-income communities.”). ↑

-

See, e.g., Jason Hickel, What Does Degrowth Mean? A Few Points of Clarification, 18 Globalizations 1105, 1106 (2021) (“Degrowth is a planned reduction of energy and resource throughput designed to bring the economy back into balance with the living world in a way that reduces inequality and improves human well-being.”); Nicholas F. Stump, Ecosocialism, Degrowth, and Global South Thought: Critical Legal Transformations, 49 Wm. & Mary Envt’l Pol’y Rev. 367, 371–72 (2025) (describing the transformational elements of degrowth). ↑

-

See Jordan Cheung, Explainer: What is Doughnut Economics?, Earth.org (Oct. 25, 2021), https://earth.org/what-is-doughnut-economics [https://perma.cc/E3VU-ZQYY] (“By rethinking our systems, the goal of national and global economies can be changed from simply increasing GDP to creating a society that can provide enough materials and services for everyone while utilising resources in a way that does not threaten our future security and prosperity.”). ↑

-

Klein, supra note 18, at 344–45 (“The shift from one power system to another must be more than a mere flipping of a switch from underground to aboveground. It must be accompanied by a power correction in which the old injustices that plague our societies are righted once and for all.”); see, e.g., Stump, supra note 21, at 371 (“An internationalist ecosocialism foregrounds global system change, national liberation, ‘climate debt reparations’ for the Global South, and the broader end to colonialism, imperialism, and interventionism.”); see generally Amna Akbar, Demands for a Democratic Political Economy, 134 Harv. L. Rev. F. 90 (2020) (tying together demands for racial, economic, and environmental justice); Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò, Reconsidering Reparations (2022) (arguing for transformative climate reparations as reparations for slavery and colonialism). ↑

-

Bratspies, supra note 20, at 6. ↑

-

E.g., Rhiana Gunn-Wright, A Green New Deal for All of Us, in All We Can Save: Truth, Courage, and Solutions for the Climate Crisis 92, 96–100 (Ayana Elizabeth Johnson & Katharine K. Wilkinson, eds., 2020) (arguing that “economic mobilization without a clear focus on justice and equity is, in fact, a danger—both to marginalized people and to our ability to effectively mitigate the climate crisis”); Naomi Klein, On Fire, in All We Can Save, supra at 39, 47 (arguing that while not “every climate policy must dismantle capitalism . . . we will not get the job done unless we are willing to embrace systemic economic and social change”). ↑

-

See, e.g., Obligations of States supra note 10, at ¶¶ 382–84 (highlighting the need to address the human rights risks faced by women, children, and Indigenous Peoples in the face of climate change); Climate Emergency and Human Rights, supra note 9, at ¶¶ 595–96 (noting the differentiated climate risks faced by marginalized communities and the legal obligations to address these risks in all elements of climate action); see also, e.g., Kate R. Finn & Christina A.W. Stanton, The (Un)just Use of Transition Minerals: How Efforts to Achieve a Low-Carbon Economy Continue to Violate Indigenous Rights, 33 Colo Envt’l L. J. 341, 357 (2022) (“Human rights treaty bodies . . . have articulated the connection between human rights, county obligation, and corporate behavior. In 2011, CERD articulated that the United States and Canada had an affirmative duty to prevent global human rights abuses by corporations licensed in their countries.”). ↑

-

See, e.g., Xiye Bastida, Calling In, in All We Can Save, supra note 25, at 3, 7 (urging that one does not “have to know the details of the science to be part of the solution,” as climate change is an issue for everyone). ↑

-

For example, ensuring adaptation measures that protect Lower Manhattan from sea-level rise, while not addressing flood risk in low-lying neighborhoods in Houston, would ring hollow. See James A. Goldston, Climate Litigation through an Equality Lens, in Litigating the Climate Emergency: How Human Rights, Courts, and Legal Mobilization Can Bolster Climate Action 132, 140 (César Rodríguez-Garavito, ed. 2023) (“But ethics don’t always drive law and politics. Thankfully, applying an equality lens to climate litigation is not just the right thing to do; it’s also more effective.”). ↑

-

E.g., Ayana Elizabeth Johnson & Katharine K. Wilkinson, Begin, in All We Can Save, supra note 25, at xvii, xxi (recounting how Eunice Newton Foote’s theory that changes in carbon dioxide in the atmosphere could affect global temperature years was made years before John Tyndall’s work, which is often credited as the foundation of climate science); Sheri Mitchell, Indigenous Prophecy and Mother Earth, in All We Can Save, supra note 25, at 16, 23 (arguing that a lack of diversity under a “patriarchal colonial paradigm” has had a ”suffocating impact on creative intelligence,” particularly within science); see also, e.g., Leah Penniman, Black Gold, in All We Can Save, supra note 25, at 301 (“[Black] families fled the red clays of Georgia for good reason—the memories of chattel slavery, sharecropping, convict leasing, and lynching were bound up with our relationship to the Earth. For many of our ancestors, freedom from terror and separation from the soil were synonymous.”). ↑

-

Klein, supra note 18, at 328–32. ↑

-

Id. ↑

-

See, e.g., Majekolagbe, supra note 20, at 42–43, 68–69 (offering “key characteristics of what should be considered just in the context of climate change-focused sustainability transition”). ↑

-

Alfred, supra note 20, at 26. ↑

-

Id. at 27. ↑

-

Elizabeth J. Kennedy, Equitable, Sustainable, and Just: A Transition Framework, 64 Ariz. L. Rev. 1045, 1051 (2022). ↑

-

U.N. Secretary-General, Synthesis Report on Opportunities, Best Practices, Actionable Solutions, Challenges, and Barriers Relevant to Just Transition and the Full Realization of Human Rights for All People, ¶ 18, U.N. Doc. A/HRC/60/52 (Advance Edited Version) (Sept. 1, 2025). ↑

-

See also Bratspies, supra note 20, at 31–33 (describing the New York City local laws that enable Renewable Rikers as a “just transition model”). ↑

-

See The Causes of Climate Change, NASA (Oct. 23, 2024), https://science.nasa.gov/climate-change/causes [https://perma.cc/6UGN-Q9ND] (explaining how carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, chlorofluorocarbons, and water vapor, all released through different kinds of human activities, contribute to climate change); see also Katharine Hayhoe, Saving Us: A Climate Scientist’s Case for Hope and Healing in a Divided World 39–48 (2021) (describing the psychological hurdles to addressing climate change). ↑

-

See Michael Murray Lawrence, ‘Polycrisis’ May be a Buzzword, but it Could Help us Tackle the World’s Woes, Conversation (Dec. 11, 2022), https://theconversation.com/polycrisis-may-be-a-buzzword-but-it-could-help-us-tackle-the-worlds-woes-195280 [https://perma.cc/348J-24QY] (describing how the global crises that make up the “polycrisis,” including climate change, “are interconnected, entwining and worsening one another”). ↑

-

See Aronoff et al., supra note 16, at 5 (arguing that “the most effective way to slash emissions and cope with climate impacts in the next decade is through egalitarian policies that prioritize public goals over corporate profits, and target investments in poor, working class, and racialized communities”). ↑

-

See Maxine Burkett, Climate Reparations, 10 Melb. J. Int’l L. 509, 518 (2009) (explaining the practical limitations of courts in taking an individualized approach to mass abuse cases). ↑

-

See Horst W. J. Rittel & Melvin M. Webber, Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning, 4 Pol. Sci. 155, 160–67 (1973) (defining and elaborating the characteristics of “wicked problems” in public policy, which tend to be multi-faceted and lack ready solutions). ↑

-

Pablo de Grieff, Justice and Reparations, in The Handbook of Reparations 451, 454 (Pablo de Grieff, ed. 2006); see also César Rodríguez-Garavito, Litigating the Climate Emergency: The Global Rise in Human Rights-Based Litigation for Climate Action, in Litigating the Climate Emergency, supra note 28, at 1, 36 (“[T]he liability model cannot adequately address structural injustices like climate change and economic inequality.”); Eric K. Yamamoto, Racial Reparations: Japanese American Redress and African American Claims, 40 B.C. L. Rev. 477, 488 (1998) (“[The litigation] paradigm works poorly where, over time, members of a group act to preserve that group’s system of dominance and privilege by denigrating other groups and excluding other groups’ members from housing, businesses, jobs and political and social opportunities; that is, situations of systemic racial oppression.”). ↑

-

Lisa Magarell, Reparations for Massive or Widespread Human Rights Violations: Sorting out Claims for Reparations and the Struggle for Social Justice, 22 Windsor Y.B. Access Just. 85, 90 (2003). ↑

-

See Burkett, supra note 41, at 510 (“The very nature of climate change defies a comfortable parsing of familiar claims and remedies. . . . Effective compensation cannot occur in a vacuum, and disparate judges or jurisdictions should not determine the fate of the climate vulnerable.”); see also Magarell, supra note 44, at 90 (arguing even though a policy approach to reparations may be “less comprehensive” to individuals as opposed to court-ordered reparations, “such a program can be more attentive to the whole universe of victims, overcome the circumstantial and limited nature of access to court judgments, more fully relate collective and individual measures, and involve broader segments of society in the process of reparations itself.”). ↑

-

E.g., Yamamoto, supra note 43, at 508 (explaining how “[l]egal obstacles, such as the statute of limitations, justiciability and causation,” have been used to preclude “actual claims,” specifically for African American reparations); John E. Bonine, Removing Barriers to Justice in Environmental Litigation, 1 Rutgers Int’l L. & Hum. Rts. J. 100, 102–13 (2021) (discussing standing doctrine as a barrier in environmental litigation); Carlotta Garofalo, ‘Foot in the Door’ or ‘Door in the Face’? The Development of Legal Strategies in European Climate Litigation between Structure and Agency, 29 Eur. L. J. 340, 348–53 (2023) (discussing standing and justiciability as barriers for European climate litigation); Magarell, supra note 44, at 90 (criticizing “the circumstantial and limited nature of access to court judgments” for addressing systemic problems). ↑

-

See Burkett, supra note 41, at 519–20 (describing the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights’ reluctance to take on the first climate human rights petition and comparing that reluctance to that of US domestic courts and other courts that “are also deferring to political processes”); Juliana v. United States, 947 F.3d 1159, 1175 (9th Cir. 2020) (remanding the climate case to the district court with instructions to dismiss on standing grounds); Case C-565/19 P, Armando Carvalho & Others v. Parliament & Council, ECLI:EU:C:2021:252 (dismissing a European climate case on standing grounds); Garofalo, supra note 46, at 351–53 (discussing cases in which “the justiciability barrier ha[d] to do with the political content of the remedy requested in climate cases”). ↑

-

E.g., Burkett, supra note 41, at 521 (“Even if legal avenues provide more than piecemeal approaches and remedies, they certainly will not get to the moral challenges that a reparations effort can address, both in process and content. Threats of lawsuits, for example, will not lead to a remedy that is forward-looking and holistic.”); see also Yamamoto, supra note 43, at 508 (“The traditional paradigm’s limitations also deprived the claims of their historical force and obscured their significance for a racially divided America.”). ↑

-

See, e.g., Ben Batros & Tessa Khan, Thinking Strategically about Climate Litigation, in Litigating the Climate Emergency supra note 28, at 97, 106 (noting several critiques of litigation, including that it is anti-democratic, elitist, and ineffective). ↑

-

See Helen Duffy, Strategic Human Rights Litigation 5 (2018) (“Litigation may have serious repercussions for victims, families and communities, and for human rights causes, if backlash compounds problems rather than presenting solutions.”). ↑

-

Burkett, supra note 41, at 520. ↑

-

Climate Acton Network et al., supra note 6, at 1. ↑

-

Climate Change Litigation Database, Sabin Ctr. Climate Change L., https://climatecasechart.com [https://perma.cc/64QW-D5HD] (last visited July 7, 2025). ↑

-

Rights-Based Climate Litigation Cases since 2005, Climate L. Accelerator, https://clxtoolkit.com/map [https://perma.cc/7ZUR-4S2C] (last visited July 7, 2025). ↑

-

This reflects all of the cases brought under such statutes on behalf of such individuals and communities listed in these databases as of September 2024, when the research was conducted. Databases are on file with the Columbia Human Rights Law Review. ↑

-

Complaint for Declaratory and Injunctive Relief at 89–92, Juliana v. United States, No. 6:15-cv-01517-TC (D. Or. 2015). ↑

-

R (oao Friends of the Earth) v. Secretary of State for Business Energy and Industrial Strategy, Sabin Ctr. Climate Change L., https://www.climatecasechart.com/document/r-oao-friends-of-the-earth-v-secretary-of-state-for-business-energy-and-industrial-strategy_0458 [https://perma.cc/QG7U-ADQ3] (last visited Sept. 30, 2025). ↑

-

ADPF 746 (Fires in the Pantanal and the Amazon Forest), Sabin Ctr. Climate Change L., https://www.climatecasechart.com/document/adpf-746-fires-in-the-pantanal-and-the-amazon-forest_5747?id=adpf-746-fires-in-the-pantanal-and-the-amazon-forest-judgment_6f63 [https://perma.cc/CZV9-HEJN] (last visited Oct. 1, 2025); Arayara Association of Education and Culture and Others v. FUNAI, Copelmi Mineração Ltda. and FEPAM (Mina Guaíba Project and Affected Indigenous Communities), Sabin Ctr. Climate Change L., https://www.climatecasechart.com/document/arayara-association-of-education-and-culture-and-others-v-funai-copelmi-mineracao-ltda-and-fepam-mina-guaiba-project-and-affected-indigenous-communities_be97 [https://perma.cc/3G5R-RRRP] (last visited Oct. 1, 2025). ↑

-

Kang et al. v. KSURE and KEXIM, Sabin Ctr. Climate Change L., https://www.climatecasechart.com/document/kang-et-al-v-ksure-and-kexim_b51c [https://perma.cc/W2C2-NC3L] (last visited Oct. 1, 2025). ↑

-

Maria Khan et al. v. Federation of Pakistan et al., Sabin Ctr. Climate Change L., https://www.climatecasechart.com/document/maria-khan-et-al-v-federation-of-pakistan-et-al_3ca5 [https://perma.cc/J8YE-PH8C] (last visited Oct. 1, 2025). ↑

-

Friends of the Irish Environment v. Ireland, [2019] IEHC 747, Judgment, ¶ 26 (Ir. High Ct. Sept. 19); see generally Friends of the Irish Environment v. Ireland, Sabin Ctr. Climate Change L., https://www.climatecasechart.com/document/friends-of-the-irish-environment-v-ireland_c37f [https://perma.cc/GXQ2-8XQD] (last visited Oct. 1, 2025) (providing a summary of case, a procedural background, and links to court decisions, among other things). ↑

-

ADPF 746 (Fires in the Pantanal and the Amazon Forest), Sabin Ctr. Climate Change L., https://www.climatecasechart.com/document/adpf-746-fires-in-the-pantanal-and-the-amazon-forest_5747?id=adpf-746-fires-in-the-pantanal-and-the-amazon-forest-judgment_6f63 [https://perma.cc/CZV9-HEJN] (last visited Oct. 1, 2025). ↑

-

E.g., Juliana v. United States, 947 F.3d 1159, 1175 (9th Cir. 2020) (case brought by 21 youth plaintiffs); ENVironnement JEUnesse v. Procureur General du Canada, Sabin Ctr. Climate Change L., https://www.climatecasechart.com/document/environnement-jeunesse-v-procureur-general-du-canada_edc9 [https://perma.cc/M29U-LMV7] (last visited Oct. 2, 2025) (case brought by/on behalf of Quebec residents under the age of 35); Duarte Agostinho and Others v. Portugal and 32 Other States, Sabin Ctr. Climate Change L., https://www.climatecasechart.com/document/duarte-agostinho-and-others-v-portugal-and-32-other-states_e05d [https://perma.cc/QY8C-L6ZK] (last visited Oct. 12, 2025) (case brought by youth/child plaintiffs). ↑

-

Depending on the domestic law of the country concerned, these groups included “marginalized communities,” “economically disadvantaged populations,” “workers,” and “low income households.” ↑

-

E.g., ADPF 746 (Fires in the Pantanal and the Amazon Forest), Sabin Ctr. Climate Change L., https://www.climatecasechart.com/document/adpf-746-fires-in-the-pantanal-and-the-amazon-forest_5747?id=adpf-746-fires-in-the-pantanal-and-the-amazon-forest-judgment_6f63 [https://perma.cc/CZV9-HEJN] (last visited Oct. 1, 2025) (“The case highlights the economic and social impacts of the fires, especially for the native communities of the Pantanal, as well as the impacts of fires on the health of animals and the population, even more aggravated by the COVID-19 pandemic.”). ↑

-

E.g., Maria Khan et al. v. Federation of Pakistan et al., Sabin Ctr. Climate Change L., https://www.climatecasechart.com/document/maria-khan-et-al-v-federation-of-pakistan-et-al_3ca5 [https://perma.cc/J8YE-PH8C] (last visited Oct. 1, 2025) (case brought by “a coalition of women”). ↑

-

E.g., In re Tax Benefits for Aviation, Sabin Ctr. Climate Change L., https://www.climatecasechart.com/document/in-re-tax-benefits-for-aviation_754d [https://perma.cc/CCT8-SEYZ] (last visited Oct. 12, 2025) (a case brought by an applicant with multiple sclerosis). ↑

-

Annalisa Savaresi & Joana Setzer, Rights-Based Litigation in the Climate Emergency: Mapping the Landscape and New Knowledge Frontiers, 13 J. Hum. Rts. & Env’t 7, 15 (2022). ↑

-

Friends of the Irish Environment v. Ireland, [2019] IEHC 747, Judgment, ¶ 26 (Ir. High Ct. Sept. 19); see generally Friends of the Irish Environment v. Ireland, Sabin Ctr. Climate Change L., https://www.climatecasechart.com/document/friends-of-the-irish-environment-v-ireland_c37f [https://perma.cc/GXQ2-8XQD] (last visited Oct. 1, 2025) (providing a summary of case, a procedural background, and links to court decisions, among other things). ↑

-

Arayara Association of Education and Culture and others v. FUNAI, Copelmi Mineração Ltda. and FEPAM (Mina Guaíba Project and Affected Indigenous Communities), Sabin Ctr. Climate Change L., https://www.climatecasechart.com/document/arayara-association-of-education-and-culture-and-others-v-funai-copelmi-mineracao-ltda-and-fepam-mina-guaiba-project-and-affected-indigenous-communities_be97? [https://perma.cc/3G5R-RRRP] (last visited Oct. 1, 2025). ↑

-

La Rose v. Her Majesty the Queen, Sabin Ctr. Climate Change L., https://www.climatecasechart.com/document/la-rose-v-her-majesty-the-queen_7e6f [https://perma.cc/3Y4Y-5ZCL] (last visited Oct. 1, 2025). ↑

-

Motion for Authorization to Institute a Class Action and Obtain the Status of Representative (Art. 574 C.C.P.), [2023] QCCS 105, ¶ 6 (S.C. Can.); see generally ENVironnement JEUnesse v. Procureur General du Canada, Sabin Ctr. Climate Change L., https://www.climatecasechart.com/document/environnement-jeunesse-v-procureur-general-du-canada_edc9 [https://perma.cc/M29U-LMV7] (last visited Oct. 2, 2025) (providing a summary of case, a procedural background, and links to court decisions, among other things). ↑

-

Climate Emergency and Human Rights, supra note 9; Zraick & Simons, supra note 10. ↑

-

Cf. Maria Antonia Tigre, “Small” Voices, Big Wins: Analyzing Remedies in Children’s Climate Cases, 82 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 1009, 1041–42 (2025) (describing how remedies in youth climate cases contributed to the recognition of new rights or rights frameworks). ↑

-

Cf. id. at 1038 (describing how remedies requiring youth participation in climate policy “elevated the procedural rights of youth and acknowledged their legitimacy as democratic actors in shaping environmental governance”). ↑

-

See generally Táíwò, supra note 23 (making the case for climate reparations as racial reparations). ↑

-

Burkett, supra note 41, at 521. ↑

-

Batros & Khan, supra note 49, at 99. ↑

-

Duffy, supra note 50, at 4; see, e.g., Beth Van Schaack, With All Deliberate Speed: Civil Human Rights Litigation as a Tool for Social Change, 57 Vand. L. Rev. 2305, 2306 (2004) (“[H]uman rights advocates share the ambitions of practitioners of ‘public impact’ litigation in using judicial processes to transcend the dispute between individual litigants, advance a particular political cause or agenda, and produce lasting and systemic changes in countries where human rights violations occur.”); Cẹ́sar Rodríguez-Garavito, Climate Change on Trial: Mobilizing Human Rights Litigation to Accelerate Climate Action 4 (2025) (describing the way that human rights-based climate “lawsuits and rulings have proliferated and articulated new legal norms around the world” and “shaped climate governance”); Christina Voigt, Foreword, in The Cambridge Handbook on Climate Litigation xiii, xiii (Margarethe Wewerinke-Singh & Sarah Mead, eds., 2025) (describing litigation’s expected “seminal role in global efforts to combat dangerous climate change”). ↑

-

See Yamamoto, supra note 43, at 509–10 (recognizing that reparations are the product of “some formal instrument” and that a “court pronouncement . . . provides a recognizable vehicle”). ↑

-

Id. at 493. ↑

-

Abigail Dillen, Litigating in a Time of Crisis, in All We Can Save, supra note 25, at 51, 58. ↑

-

See Paul Rink, Conceptualizing U.S. Strategic Climate Rights Litigation, 49 Harv. Envt’l L. Rev. 149, 193 (2025) (“Open access to courtroom proceedings can spur on-the-ground change even when cases are unsuccessful in court.”). ↑

-

Id. at 191. ↑

-

Id. at 192. ↑

-

Id. at 193. ↑

-

Id. at 194. ↑

-

Juan Auz, The Political Ecology of Climate Remedies in Latin America and the Caribbean: Comparing Compliance between National and Inter-American Litigation, 16 J. Hum. Rts. Practice 182, 183 (2024). ↑

-

Camila Bustos, Implementing Climate Remedies, 78 Vand. L. Rev. (forthcoming 2025) (manuscript at 9) (on file with the Columbia Human Rights Law Review). ↑

-

Burkett, supra note 41, at 522. ↑

-

Id. at 511. ↑

-

Id. at 528. ↑

-

de Grieff, supra note 43, at 454–66. ↑

-

Duffy, supra note 50, at 60. ↑

-

Id. at 63–64. ↑

-

Id. at 267. ↑

-

Juan Auz & Marcela Zúñiga, Remedies, in The Cambridge Handbook on Climate Litigation, supra note 79, at 445, 456. ↑

-

E.g., Paolo Davide Farah & Imad Antoine Ibrahim, Urgenda vs. Juliana: Lessons for Future Climate Change Litigation Cases, 84 U. Pitt. L. Rev. 547, 576–79 (2023) (advocating for future climate lawsuits to “attempt to target specific harmful policies and regulations”). ↑

-

Auz, supra note 88, at 200. ↑

-

See Batros & Khan, supra note 49, at 112 (“[I]t is necessary to play for how to implement the decision (what is required in the days, months, and years after the judgment) if a legal victory is not to be a hollow one.”). ↑

-

Eric K. Yamamoto, Friend, Foe, or Something Else: Social Meanings of Redress and Reparation, 20 Denv. J. Int’l L. & Pol’y 223, 227 (1992). ↑

-

Yamamoto, supra note 43, at 492. ↑

-

See, e.g., Randall S. Abate, Anthropocene Accountability Litigation: Confronting Common Enemies to Promote a Just Transition, 46 Colum. J. Envt’l. L. 225, 232, 265–88 (2021) (advocating for strategic collaboration against common enemies “to phase out reliance on fossil fuels and factory farms and promote a just transition by drawing on past successes and current opportunities in related contexts”). ↑

-

Lisa Vanhala, The Social and Political Life of Climate Change Litigation: Mobilizing the Law to Address the Climate Crisis, in Litigating the Climate Emergency, supra note 28, at 84, 92. ↑

-

Batros & Khan, supra note 49, at 109. ↑

-

Id. ↑

-

Id. at 113–15. ↑

Climate Equality Litigation and Transformative Justice

Monica Visalam Iyer

Perhaps the most optimistic view of the climate crisis is that it presents an opportunity, or even a necessity, to forge a new vision of the world that we share. If we are to face the threat of global warming, this must be done not only in a manner that is environmentally sustainable, but also in a way that reckons with historical and structural inequalities and provides opportunities for all people, as well as nature, to thrive. However, while climate litigation may provide an important tool for addressing some of the disproportionate impacts that climate change has on historically marginalized groups or individuals, there is significant skepticism about the power of such litigation to effect transformative or systemic change. This essay provides a brief overview of the advocacy that calls for a just transition that represents a break with past systems and structures of inequality and examines why litigation has been thought inadequate to contribute to that change. Then, calling on climate litigation databases, it examines the remedies sought and granted in climate cases brought under equal protection laws to determine whether, and if so how, any such cases have offered the possibility of addressing historic or structural inequalities. Finally, drawing on the literature of reparative and transformative justice, it will explore whether there are avenues through which climate litigants might be able to seek more transformative outcomes. Ultimately, the essay argues that well-crafted remedy requests and carefully considered litigation strategies can enable climate equality litigation to drive transformative justice.

Table of Contents

I. A New World from the Ashes? Climate Change as Opportunity for Transformation 290

II. The (Im)Possibility of Transformational Change Through Litigation 295

III. Climate Equality Litigation Efforts thus Far 299

IV. Possibilities for the Future 305

From many places around the world, and especially from the United States, the climate future in 2025 looks bleak. Record summer heat pummeled people from Pakistan[1] to Punxsutawney.[2] Climate scientists have warned that global average temperatures will soon warm beyond the target set in the Paris Agreement[3] and that a range of climate tipping points are imminent.[4] The Trump Administration has withdrawn from the Paris Agreement and has sought a significant rollback of domestic climate action.[5] A coalition of more than 200 civil society organizations has proclaimed that global climate negotiations are at a breaking point and “increasingly perceived as out of touch, driven by vested interests, and running out of relevance and trust.”[6] And as climate harms grow, so too does inequality. It is widely understood and acknowledged that climate change’s worst impacts will fall on individuals and groups who have already been the targets of historical discrimination and marginalization,[7] and that income and other gaps between these groups and the general population will be exacerbated by these impacts.[8]

Despite all of this bad news, however, there are points of light. In particular, in advisory rulings handed down in the summer of 2025, both the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (responding to a request from Chile and Colombia)[9] and the International Court of Justice (as requested by a unanimous resolution of the General Assembly)[10] examined the questions of States’ legal obligations to take climate action and affirmed that international law, including international human rights law, imposes significant obligations in this regard. There are also people who refuse to give up hope that better climate outcomes are possible and who seek to turn “fear into action.”[11] Many of these advocates argue that as climate change presents the necessity of transformational change, it also provides an opportunity to pursue transformations beyond energy use or consumption habits and to address systems of inequality and injustice.[12] But where will these kinds of transformations come from? With climate negotiations alleged to have “systematically failed to deliver climate justice”[13] and domestic political leaders largely unwilling to stray too far from the interests of wealthy and powerful fossil fuel constituencies,[14] many are turning to litigation as a last best hope for stirring climate action. At the same time, however, litigation is widely acknowledged to be an inadequate tool for achieving systemic change.[15] Is this correct? Is there any way that climate litigation can also seek to address systemic inequalities?

This essay examines a subset of climate litigation—that which already operates at the intersection of climate change harms and systemic inequalities by raising claims under equal protection laws—in order to evaluate the extent to which the remedies sought in such cases have the potential to address systemic underlying causes. In doing so, it analyzes the potential for such litigation to achieve, or contribute to the achievement of, what I refer to as transformative justice: a legal result designed to address past inequality and promote systemic change. I argue that ultimately, through carefully crafted remedy requests and broader litigation and advocacy strategies, climate equality litigation can be a vehicle of transformative justice. Part I of the essay describes calls for a climate transition that tackles inequality. Part II explores why litigation has largely been seen as unable to meaningfully contribute to such calls. Part III draws on climate litigation databases to identify “climate equality” cases and the remedies sought in such cases. Finally, Part IV concludes with some reflections, drawing in particular on reparations literature, on how climate equality litigation might contribute to transformative change.

I. A New World from the Ashes? Climate Change as Opportunity for Transformation

A number of climate change advocates now insist that climate change presents both an opportunity and a necessity for fundamental global social and economic transformation.[16] Responding to this emergency provides a chance to abandon exploitative and unequal economic and social models, which have been predicated on hierarchies of human value and commodification of nature, in favor of more just and cooperative societies that stay within planetary boundaries.[17] One of the most prominent of these advocates is Naomi Klein, who says in the introduction to her seminal climate book, This Changes Everything, that “climate change . . . could become a galvanizing force for humanity, leaving us all not just safer from extreme weather, but with societies that are safer and fairer in all kinds of ways as well.”[18] These arguments form part of the just transition discourse that calls for greater attention to workers and those who will potentially be most negatively affected in the movement away from fossil fuels,[19] but such arguments may also involve broader and more systemic transformation.[20]

Much of this discourse is focused on economic systems, as reflected, for example, in the subtitle to Klein’s book: “Capitalism vs. The Climate.” Advocates focus on the current exploitative model of global capitalism as being unsustainable. Some have called for a “de-growth” model[21] or a “doughnut economy,” which uses enough resources to ensure humans and ecosystems can thrive, but not so much that we exceed what the planet can handle.[22] But as the quote from Klein above makes clear, many advocates are also thinking beyond economic inequalities to climate change as being a chance to address other systemic inequalities that have historically been built on discrimination and prejudice against marginalized groups.[23] As Rebecca Bratspies phrases it, the “[k]ey to a just transition, as opposed merely to a transition, is the involvement of those most affected by the changes, and the intentional disruption of structural inequalities embedded in pre-existing economic and environmental policies.”[24]

In the understanding of these thinkers and advocates, as elaborated below, addressing inequalities based on race, ethnicity, indigeneity, gender, age, disability status, sexual orientation, gender identity, and other factors is a necessary part of climate action. These inequalities are so inextricably intertwined with the economic system that perpetuates the climate crisis that we cannot address one without addressing the other. Failing to address these inequities will lead to a failure of climate action. Essentially, there is no way to construct a system that ends the unsustainable commodification and exploitation of the earth while continuing unsustainable commodification and exploitation of humans.[25] Failing to address these inequalities will also mean a failure to comply with existing human rights obligations for many countries, as multiple international courts have found that States have obligations to take climate action in a manner that takes into account intersectional inequalities.[26] Further, the global scale of the problem of climate change is such that everyone needs to be empowered to take climate action, and addressing systemic inequalities is a means of bringing everyone into solutions.[27] It is also a means of ensuring that there is no backlash against climate action that may be seen as privileging the concerns of elites. Transformative climate action that addresses systemic inequalities can enjoy broad popular support, while climate action that only addresses the concerns of those who already enjoy power will face popular resentment.[28] Relatedly, historically marginalized groups may offer new ways of thinking about climate problems and new adaptation tools and techniques; perpetuating systems of marginalization and discrimination forecloses our access to those solutions.[29] Klein documents, for example, how Indigenous opposition to fossil fuel exploitation created a new sense of mobilization and possibilities for coalition building in Canada and “sparked a national discussion about the duty to respect First Nation Legal Rights.”[30] This movement opened up possibilities for reevaluation of the relationship between Indigenous communities and settler-colonial states and new opportunities for addressing historical wrongs in the treatment of these communities.[31]