WHEN LIBERTY IS THE EXCEPTION: THE SCATTERED RIGHT TO BOND HEARINGS IN PROLONGED IMMIGRATION DETENTION

Freya Jamison

Table of Contents

Introduction 148

I. The Constitutional Problem of Indefinite Immigration

Detention 150

A. The Prolonged and Potentially Indefinite Incarceration of

Noncitizens Under the Immigration Detention Statutes 150

B. The Supreme Court’s Jurisprudence on the Due Process

Right to a Bond Hearing in Prolonged Immigration Detention 152

C. The Fractured State of Due Process Analysis Across District

and Circuit Courts 156

II. How District Courts Adjudicate Immigrant Detainees’

Habeas Claims 162

A. Source Data 163

B. Analysis 164

1. Habeas Filings Are Timed to Court-Recognized Benchmarks 164

2. Habeas Outcomes Varied for Noncitizens Detained for

Similar Periods 165

3. Delay or Bad Faith by the Petitioner is More Predictive of

Habeas Outcome than Detention Length 169

4. Lengthy Adjudication Times Exacerbate Due Process

Violations 172

5. Jennings Did Not Change the Grant Rate Around the Six

Month Detention Mark 174

III. A Better Approach to Reasonableness 176

A. Eliminate Factors that Speak to Bond Eligibility from the Constitutional Due Process Analysis 177

B. Streamline the Due Process Inquiry by Establishing a Nationwide Presumption of a Due Process Violation Before Six Months of

Detention 182

Conclusion 185

Introduction

Despite the Supreme Court’s promise that “liberty is the norm, and detention . . . without trial is the carefully limited exception,”[1] thousands of noncitizens languish in prisons around the country pending the outcome of their immigration proceedings without the government ever having to prove to a judge that their detention is necessary.[2] When the government incarcerates someone on a criminal charge, it must justify that person’s pretrial detention at a bond hearing.[3] When the government incarcerates an immigrant in preparation for their deportation, however, that immigrant does not enjoy the same fundamental protections. Immigration detention is meant to be nonpunitive,[4] but, in reality, the government holds immigrant detainees in prison-like conditions,[5] often for years,[6] while detainees exercise their statutory right to prove that they are entitled to remain in the United States.

Recognizing that this practice raises due process concerns, the Second and Ninth Circuits interpreted the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA)’s mandatory detention provisions to include an implicit right to a bond hearing after six months of detention.[7] The Supreme Court found this construction of the statute impermissible in a 2018 decision, Jennings v. Rodriguez,[8] but left open the possibility that, after some length of detention, continued incarceration without a bond hearing becomes unconstitutional. This Note exposes the problems created by the Supreme Court’s failure in Jennings to provide guidance to lower courts on how to analyze allegations that indefinite immigration detention without a bond hearing violates constitutional due process. Without a centralized test, district and circuit courts have been left to develop their own approaches to answering this question, meaning that the process afforded to any given detainee depends on chance and geography.

This Note examines how the various constitutional tests operate in practice and suggests reforms to make those tests both more equitable and more efficient. Part I explains that, while it is undisputed that constitutional due process applies to deportation proceedings, there is no universal rule governing whether and when the Constitution requires a bond hearing for immigrant detainees. Part I examines the Jennings decision and prior Supreme Court precedent, then catalogues the different approaches that lower courts have taken in the wake of Jennings. Part II analyzes these tests and the 249 habeas petitions decided under them in federal district courts in the decade between January 1, 2010 and December 31, 2019. The data examined in Part II shows that the current tests produce lengthy adjudications and disparate outcomes in similar cases. Part III then proposes two reforms that can be implemented at the district and circuit court levels: (1) reserving consideration of petitioner delay for bond hearings conducted by Immigration Judges (IJs), and (2) instituting a presumption of a due process violation after the length of a noncitizen’s detention reaches a certain threshold, at most six months.

I. The Constitutional Problem of Indefinite Immigration Detention

A. The Prolonged and Potentially Indefinite Incarceration of Noncitizens Under the Immigration Detention Statutes

To ensure the appearance of noncitizens at their deportation proceedings, Congress amended the immigration laws in 1995 to provide for the executive detention of certain noncitizens.[9] Today, four provisions of the INA authorize the detention of certain categories of individuals until their removal: (1) noncitizens who fail a credible fear screening by an asylum officer (“§ 1225(b)(1) detainees”),[10] (2) noncitizens arrested on a warrant issued by the Attorney General pending a decision on their removability (“§ 226(a) detainees”),[11] (3) noncitizens who are inadmissible based on a prior criminal conviction for certain enumerated offenses (“§ 1226(c) detainees”),[12] and (4) noncitizens with final orders of removal (“§ 1231(a) detainees”).[13] The immigration laws allow for certain detainees to be released on bond,[14] but detention under § 1226(c) and § 1225(b)(1) is mandatory.[15] This Note focuses only on the constitutional rights of § 1225(b)(1) and § 1226(c) detainees because their cases make up the vast majority of suits challenging the constitutionality of prolonged immigration detention.[16]

Although immigration detention is intended to be a temporary measure while the government prepares to deport a detainee, in reality detention can be lengthy and even indefinite. The cases of Joseph Hechavarria and Bright Falodun are illustrative. Mr. Hechavarria, a Jamaican citizen, has been a lawful permanent resident of the United States since 1987.[17] He is married to an American citizen and suffers from a serious renal disease that requires “frequent life-sustaining medical services.”[18] In July 2013, he was taken into the custody of the Department of Homeland Security pursuant to the agency’s § 1226(c) authority and was incarcerated at the Buffalo Federal Detention Facility (BFDF) in Batavia, New York.[19] Mr. Hechavarria remained at BFDF for more than five years while he pursued “opportunities for administrative and judicial review of legitimate claims in his underlying proceedings [challenging his deportation order].”[20] Similarly, Mr. Falodun, a native of Nigeria and lawful permanent resident of the United States, was detained at BFDF under the same detention statute for more than four years while his claim for withholding of removal was pending in administrative and federal courts.[21] Mr. Falodun’s case involved novel legal questions that resulted in lengthy appeals.[22] Although immigration detention is temporary by purpose, these two men’s lived experiences expose the inefficiencies of the deportation process.

Immigrant detainees have few options to challenge their prolonged detention. § 1226(a) detainees and certain § 1225(b)(1) detainees may petition the government for discretionary parole,[23] which has become a less viable option under the Trump administration. In January 2017, President Trump issued Executive Order 13767, which technically limited parole to emergency situations,[24] but in practice constituted a “blanket denial” of parole for all detained immigrants.[25] Parole decisions are entirely discretionary and are not appealable to any agency authority or federal court.[26]

With parole effectively foreclosed as a remedy for prolonged detention for many detainees and legally foreclosed for others, detainees must turn to their second option: challenging the constitutionality of their detention through a petition for habeas corpus in federal court.[27] Immigrant detainees have successfully used habeas petitions as a vehicle to bring procedural due process claims, alleging that their continued detention without a bond hearing violates the Fifth Amendment.[28] If a federal judge finds a due process violation, the case then typically moves to immigration court, where an IJ holds a bond hearing to determine whether the noncitizen may be released from custody pending their actual deportation.[29]

B. The Supreme Court’s Jurisprudence on the Due Process Right to a Bond Hearing in Prolonged Immigration Detention

Although the Supreme Court has stated that asylum seekers who are physically present in the United States have due process rights under the Fifth Amendment,[30] it has never clarified whether (and under what circumstances) that includes the right to a bond hearing in immigration detention. The Court has addressed the constitutionality of immigration detention twice and took two very different approaches to the question.

Zadvydas v. Davis involved a challenge to 8 U.S.C. § 1231(a)(6), a provision of the INA authorizing immigration detention beyond the 90-day statutory removal period for individuals with final removal orders who could not logistically be deported (plaintiff Zadvydas, for instance, could not be removed because he was stateless and no country would grant him citizenship).[31] Relying on United States v. Salerno, Justice Breyer’s majority opinion concluded that immigration detention is subject to the same due process protections as other forms of civil detention.[32] If continued detention is not reasonably necessary to fulfill the statute’s purpose of ensuring a noncitizen’s presence at the moment of removal (because, for instance, they are stateless and cannot practically be removed), the Court reasoned, detention is not constitutionally permissible.[33] The Court concluded that after six months of § 1231(a)(6) detention, if the detainee shows that there is “no significant likelihood of removal in the reasonably foreseeable future,” the government must either rebut that showing or release the detainee.[34] The Court ultimately remanded the case for further consideration of the facts of plaintiffs’ habeas petitions.[35]

Only two years later, a plurality of the Court upheld § 1226(c)’s mandatory detention provision against a facial challenge in Demore v. Kim.[36] The challenge was raised in a habeas petition by Hyung Joon Kim, a South Korean national and lawful permanent resident of the United States who was detained by immigration authorities after his conviction for burglary and “petty theft with priors.”[37] The Court acknowledged that “the Fifth Amendment entitles aliens to due process of law in deportation proceedings,”[38] but, emphasizing the political branches’ extensive power over deportation, determined that “Congress may make rules as to aliens that would be unacceptable if applied to citizens.”[39] The plurality distinguished Zadvydas on the fact that removal was “no longer practically attainable” for the petitioners in that case, whereas Mr. Kim’s removal was still pending.[40] The Court also relied on the fact that detention under § 1226(c) was generally brief, stating that “in the majority of cases” detention lasted less than ninety days.[41] The government later admitted that this statistic was erroneous; in fact, at the time that Demore was decided, detention under § 1226(c) typically lasted 113 days if the immigrant did not appeal their underlying immigration case and nearly a year if the immigrant did appeal.[42] The Court even acknowledged that its statistic was not representative of Mr. Kim’s case, as he had been detained for six months—in the Court’s words, “somewhat longer than the average.”[43] Having found no constitutional problem, the Court denied Mr. Kim’s habeas petition.[44]

Justice Kennedy provided the crucial fifth vote against finding a due process violation in Mr. Kim’s case, but in his controlling concurrence he was unwilling to foreclose that finding in all cases. Justice Kennedy maintained that due process could require “an individualized determination as to [the detainee’s] risk of flight and dangerousness if the continued detention became unreasonable or unjustified.”[45] He stated more specifically that, were immigration officials to “unreasonabl[y] delay” the detainee’s deportation proceedings, “it could become necessary” to inquire whether the detention was actually aimed at the statute’s goals of facilitating deportation and protecting against flight risk or dangerousness.[46] Although Justice Kennedy’s concurrence preserved the possibility that due process could require a bond hearing for immigrant detainees in future cases, it provided little guidance on how to conduct that analysis, leaving district and circuit court judges to answer that question themselves.

In 2017 and again in 2018, the Supreme Court had the opportunity to definitively extend a due process right to a bond hearing to individuals in mandatory immigration detention but ultimately remanded the case without meaningful guidance for lower courts. Jennings v. Rodriguez, on appeal from the Ninth Circuit, involved a challenge by a class of:

[A]ll non-citizens within the Central District of California who: (1) are or were detained for longer than six months pursuant to [§ 1225(b)(1), § 1226(a), or § 1226(c)] pending completion of removal proceedings, including judicial review, (2) are not and have not been detained pursuant to a national security detention statute, and (3) have not been afforded a hearing to determine whether their detention is justified.[47]

The Ninth Circuit sided with the plaintiffs, affirming the district court’s permanent injunction requiring a bond hearing for class members when their detention hit six months and again every six months after that.[48]

Jennings’ procedural history before the Court was dramatic. After hearing argument on the Ninth Circuit’s constitutional avoidance construction of the INA in November 2016, the Supreme Court ordered re-argument for the subsequent term.[49] In 2017, the parties argued the merits of the underlying constitutional due process question. One month after the second oral argument, Justice Kagan recused herself from the case after discovering that she had “authorized the filing of a pleading in an earlier phase of th[e] case” in her role as Solicitor General.[50]

Ultimately, an eight-member Court reversed the Ninth Circuit, holding that it had incorrectly applied the canon of constitutional avoidance to create the six-month rule.[51] Instead of addressing the constitutional question underlying the avoidance argument, the Court remanded to the Ninth Circuit to consider the question “in the first instance.”[52] The Supreme Court also ordered the lower court to “reexamine” whether federal jurisdiction over the class action was proper in light of its ruling.[53]

C. The Fractured State of Due Process Analysis Across District and Circuit Courts

With no guidance from the Supreme Court, district and circuit courts across the country have developed their own tests to evaluate the constitutionality of immigration detention without a bond hearing. Nearly every court of appeals that has considered the question has held that, at some point, prolonged detention without a bond hearing violates due process.[54] The courts of appeals differed, however, in their approaches to resolving this constitutional issue. Only the Second and Ninth Circuits took a bright-line rule approach, mandating a bond hearing for immigrant detainees after six months of detention.[55] Their holdings were premised on constitutional avoidance logic; because indefinite detention without a bond hearing would violate due process, they reasoned, the detention statutes must be construed to contain an “implicit time limitation” of six months.[56] The Supreme Court’s decision in Jennings, however, foreclosed the bright-line rule approach as a matter of statutory interpretation, finding the canon of constitutional avoidance inapplicable because the text of § 1225(b)(1) and § 1226(c) clearly authorize detention until the end of the underlying immigration proceedings.[57] Neither the Second nor the Ninth Circuit has addressed the underlying constitutional question since Jennings,[58] though the Ninth Circuit left the six-month rule in place in the Central District of California while the case is pending on remand.[59]

The First, Third, Sixth, and Eleventh Circuits all rejected the bright-line rule construction and instead adopted fact-specific reasonableness tests to determine when detention without a bond hearing violates due process.[60] Because the Third Circuit’s holding was premised on both a constitutional avoidance reading of the statute and the underlying constitutional question, it unquestionably survived Jennings.[61] Other courts of appeals rooted their reasonableness tests solely in constitutional avoidance readings of the statute, so the status of their holdings post-Jennings is less certain.[62] Regardless, studying the reasonableness tests is useful because courts of appeals will likely find their constitutional avoidance holdings mandated by the Due Process Clause.[63] The Supreme Court’s invalidation of the six-month rule left a vacuum in the Second Circuit, so district courts within the circuit have also developed their own constitutional reasonableness tests. District judges within the Second Circuit commonly cite Sajous v. Decker[64] from the Southern District of New York and Hemans v. Searls[65] from the Western District of New York.[66] These circuit and district court tests overlap but are not entirely consistent. Table 1 summarizes the common tests.

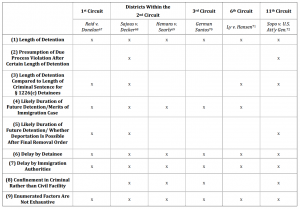

Table 1. Factors Considered in Determining Whether Continued Detention Without a Bond Hearing Is Unreasonable in Violation of Due Process

Factors (1), (2), and (3) consider the length of the noncitizens’ civil incarceration. At least three courts explicitly treat the length of detention as the most important consideration in the reasonableness inquiry.[73] The Eleventh Circuit’s analysis in Sopo further demonstrates the heavy weight that courts claim to give this factor: “The sheer length of Sopo’s detention on its own is enough to convince us that his liberty interest long ago outweighed any justifications for using presumptions to detain him without a bond inquiry.”[74] Some courts balance detention length in favor of § 1226(c) detainees when it exceeds the length of the detainee’s previous criminal sentence,[75] while others compare the length of detention against certain benchmarks, like the average times set out in Demore.[76] The consideration of detention length squares with Demore’s approval of only “brief” detention.[77]

Factors (4) and (5) speak to the estimated length of future detention, asking both how likely it is that the immigrant will be issued a final order of removal and, if that removal is ordered, whether it is technically feasible. If the noncitizen is likely to prevail on their underlying asylum or immigration claim or if their removal is impossible (for instance, because no country is willing to issue them travel documents), courts weigh these factors toward a due process violation.[78] These inquiries address Zadvydas’s warning that detention must be related to the goal of the statute, which is ensuring that the government is able to complete the removal process for noncitizens ineligible to remain in the United States.[79]

Two more factors, (6) and (7), inquire into which party, if any, is responsible for the length of detention: immigration authorities or the detainee. Courts across the board weigh delays by the government toward a finding of a due process violation.[80] The ubiquity of this factor is explained by its appearance in Demore; it is, in fact, the only factor that Justice Kennedy’s concurrence mentions specifically.[81] The tests also consider delay by the detainee, generally requiring purposeful delay in bad faith to count against the detainee.[82] Courts consider delay by the detainee in order to prevent noncitizens from “gaming the system” by filing frivolous appeals to postpone their removal[83] or prolonging their detention long enough to be released on bond, then fleeing from immigration authorities.[84] This consideration is not mandated by the Supreme Court; although the plurality in Demore did acknowledge that the length of Mr. Kim’s detention was partly due to his request for a continuance in his underlying immigration case, the plurality mentioned that fact in a broader discussion of average detention lengths and ultimately upheld the constitutionality of mandatory detention during removal proceedings.[85] It is surprising, then, that each of the reasonableness tests considers whether delay is attributable to the immigrant detainee in one form or another.

The Third and Eleventh Circuits, along with district courts within the Second Circuit, also consider factor (8): whether the conditions of confinement are meaningfully different from criminal imprisonment.[86] A petitioner in a Third Circuit case was held at the York County Prison alongside criminal defendants.[87] The Third Circuit in that case weighed that fact in the petitioner’s favor, noting that “merely calling a confinement ‘civil detention’ does not, of itself, meaningfully differentiate it from penal measures.”[88] This factor reflects a concern that non-criminal executive detention is not meant to be a punitive measure.[89]

Finally, each of the tests maintains that the listed factors are not exclusive; courts may look to additional considerations that speak to the totality of the circumstances. As the Third Circuit explained in Diop, “[r]easonableness, by its very nature, is a fact-dependent inquiry requiring an assessment of all of the circumstances of any given case.”[90] Similarly, the First Circuit clarified, “[t]here may be other factors that bear on the reasonableness of categorical detention, but we need not strain to develop an exhaustive taxonomy here. We note these factors only to help resolve the case before us and to provide guideposts for other courts conducting such a reasonableness review.”[91] Despite these disclaimers, none of the cases from the data set analyzed in Part II explicitly considered a factor not included in Table 1.

II. How District Courts Adjudicate Immigrant Detainees’ Habeas Claims

The need for a test that is applied transparently and consistently across judges, districts, and circuits is an issue of both access to justice and basic fairness. Whether or not an asylum applicant is granted asylum is already largely a function of chance.[92] Immigrants may be less likely to vigorously appeal their meritorious asylum claims if they are forced to choose between appealing from long-term confinement in punitive conditions or accepting deportation.[93] It is also more difficult to appeal meritorious claims from detention, where appellees have limited contact with the outside world, limited access to legal resources, and no ability to earn money to pay legal fees.[94] This Part analyzes a decade of quantitative data from district court decisions on immigrant detainees’ habeas petitions to determine how reasonableness tests operate in practice. Section II.A details the scope of the data analyzed. Section II.B draws trends from that data, explaining when immigrant detainees filed their habeas petitions, evaluating which factors from the reasonableness inquiries drove case outcomes, and inquiring into the effect of Jennings on habeas petition outcomes.

The analysis in this Note is based on district court opinions available on Westlaw and LexisNexis decided between January 1, 2010 and December 31, 2019 on habeas petitions from § 1226(c) and § 1225(b)(1) detainees claiming a due process right to a bond hearing from within the First, Second, Third, Sixth, and Eleventh Circuits[95]—all of the circuits where a court of appeals has recognized such a right.[96] The data includes only the decisions that were decided under reasonableness tests, so does not include petitioners in the Second and Ninth Circuits who enjoyed a bond hearing automatically after six months based on a constitutional avoidance construction of the detention statutes. In total, the data set includes 264 cases (6 from within the First Circuit, 73 from within the Second Circuit, 176 from within the Third Circuit, 2 from within the Sixth Circuit, and 7 from within the Eleventh Circuit). For each case, the data set contains information on the deciding court; the presiding judge; the petitioner’s representation status (pro se or with counsel); the detention statute the petitioner was held under; the dates of initial custody, habeas filing, and habeas decision; the outcome of the petition (whether the bond hearing request was granted or denied); and whether the deciding court considered delay by the petitioner.

The statistical analysis in Part II is limited to petitions from within the Second and Third Circuits because the vast majority of petitions originated in those regions. Fewer cases originated in the Second Circuit than the Third because immigrant detainees within the Second Circuit enjoyed an automatic right to a bond hearing after six months of detention from October 28, 2015 to March 5, 2018 under Lora.[97] While the Fifth and Ninth Circuits are each home to a large percentage of the noncitizen population of the United States,[98] neither is included because the Ninth Circuit’s injunction guaranteeing a bond hearing after six months of detention is still in place in the Central District of California pending resolution of the constitutional question,[99] and because the Fifth Circuit has never addressed the question. The variation in the number of petitions filed within each of the other circuits may be a product of the location of federal detention facilities, awareness of the availability of the habeas writ among detainees, and/or the accessibility of low cost or pro bono counsel.[100]

B. Analysis

1. Habeas Filings Are Timed to Court-Recognized Benchmarks

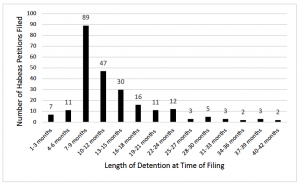

Figure 1 displays the frequency at which habeas petitions were filed at given lengths of detention. The majority of § 1225(b)(1) and § 1226(c) detainees (56%) filed their petitions between six to twelve months of detention, a time period recognized by several courts of appeals as approaching the outer limits of constitutionality.[101] Very few petitions (only 7.4%) were filed before the six-month mark. Most petitions (83%) were filed within a year and a half of detention, though several were filed more than three years after the detainee’s arrest (2%). Late filings are unsurprising given that 57% of detainees filed their habeas petitions pro se[102] and thus were less likely to be aware of the availability of habeas petitions and how and when to file them.

Figure 1. Length of Detention When Habeas Petitions Were Filed

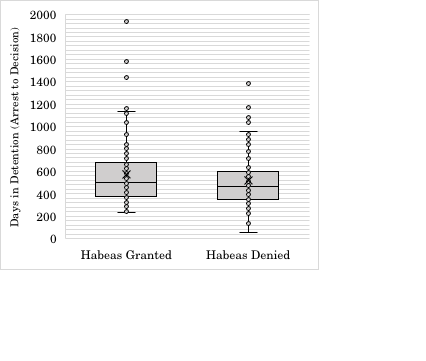

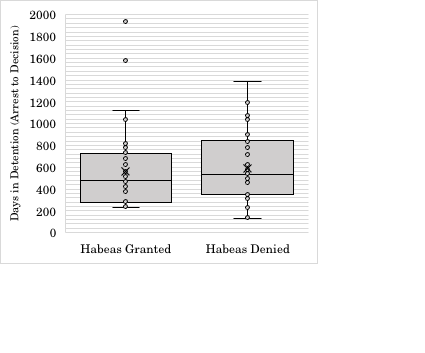

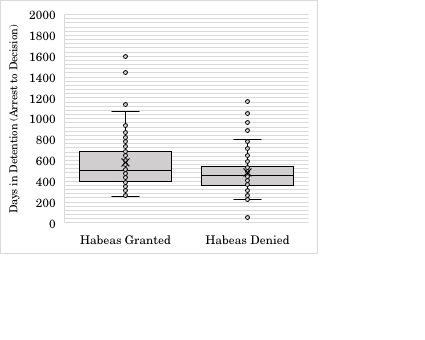

2. Habeas Outcomes Varied for Noncitizens Detained for Similar Periods

Figures 2–4 plot the outcomes of noncitizens’ habeas petitions against the total length of their detention (date of apprehension through date of habeas decision) for the entire data set (Figure 2), for courts within the Second Circuit (Figure 3), and for courts within the Third Circuit (Figure 4).[103] The plots show that one year of detention did not guarantee that a habeas petition would be granted. In fact, Figure 2 shows that the median length of detention for the subset of petitioners who were denied a bond hearing was 468 days, meaning more than half of all denials occurred in cases involving more than one year and three months of detention. 50% of all denials occurred between 352.5 and 602 days of detention (the range in the Second Circuit was 347.8–842.3 days and the range in the Third Circuit was 361–542.5 days). Figure 3 reveals that the median length of detention for denied cases was longest within the Second Circuit—530 days, or nearly a year and a half of detention. Figure 3 also shows that during periods when Lora did not mandate bond hearings within six months of detention in the Second Circuit (January 2010 to October 2015 and March 2018 to December 2019), district courts did not follow any de facto six-month rule.

Figure 2. Length of Detention and Habeas Outcomes in the Second and Third Circuits[104]

Though both the Second and Third Circuits aver that detention for more than six or twelve months raises constitutional concerns,[105] in practice, no length of detention predicted a finding of a due process violation. In fact, some habeas petitions were denied even in instances of detention without a bond hearing lasting three years or longer.[106] Consequently, factors other than length of detention drive courts’ decision making on immigrant detainees’ habeas petitions.

The disparate outcomes of two very similar cases illustrate how the length of detention is often not determinative of whether a detainee’s petition will be granted. Jose Ricardo Bayona-Castillo and Malcolm Anthony Haynes are both lawful permanent residents of the United States, and both were convicted of drug-related crimes in New Jersey state courts.[107] Because of their criminal histories, both men were detained by federal immigration authorities under § 1226(c) pending their removal.[108] Their habeas petitions were each assigned to John Michael Vazquez, United States District Judge for the District of New Jersey. At the time their petitions were decided, each man had been detained for just over a year,[109] longer than the six- and twelve-month marks deemed relevant by the Second, Third, Ninth, and Eleventh Circuits.[110] Despite these similarities, however, Judge Vazquez granted Mr. Haynes’s petition and denied Mr. Bayona-Castillo’s petition. The quality of each petitioner’s representation does not explain these contrary outcomes; Mr. Haynes represented himself in the proceedings and was successful, while Mr. Bayona-Castillo was represented by counsel and was ultimately denied relief.[111] The discrepancy is also not the result of judges giving extra leeway to pro se petitioners; of the sample of cases studied, petitions submitted by a detainee’s counsel were granted 66.3% of the time, while pro se petitions were only granted in 49.3% of cases.[112] It is clear from these cases that, in practice, yearlong detention does not predict a finding of a due process violation.

Figure 3. Length of Detention and Habeas Outcomes in the Second Circuit

Figure 4. Length of Detention and Habeas Outcomes in the Third Circuit

While some legitimate differences between cases (like disparities in when detainees file their habeas petitions) play a role in late decisions, one would certainly expect that after a year of detention without trial, one has a right to require the government to justify the necessity of continued detention. The data, as well as the cases of Mr. Bayona-Castillo and Mr. Haynes, suggest otherwise.

3. Delay or Bad Faith by the Petitioner is More Predictive of Habeas Outcome than Detention Length

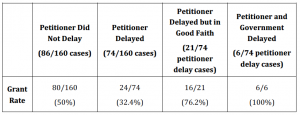

By contrast, whether the habeas court found that the petitioner delayed the final adjudication of his or her underlying immigration case correlated with habeas petition outcomes. District judges explicitly considered petitioner delay in 160 of the cases studied. Of those 160 cases, courts found that 86 petitioners were not responsible for the delays in their cases and 74 petitioners were. Table 2 indicates that when there was no finding of petitioner delay, district courts granted habeas petitions 50% of the time. When courts found petitioner delay, however, the grant rate dropped to 32.4%. In several cases, habeas courts denied relief after finding petitioner delay despite extremely lengthy detention. For instance, § 1226(c) detainee Jefferson Farray’s petition was denied despite his more than three-year detention after the court determined that the challenged detention was “prolonged by petitioner’s own pursuit of judicial review of the final order of removal.”[113] While the 50% statistic shows that petitioner delay is not the only significant factor in the due process analysis, it clearly has a substantial impact on case outcomes.

Table 2. Outcomes When the Habeas Court Considered Delay by the Petitioner

Table 2 further shows that not all delay is equal. In the six cases where courts attributed delay to both the government and the petitioner, the petitioner was victorious every time, suggesting that courts weigh delay by the government more heavily than delay by the petitioner.[114] Courts were also more lenient when they determined that a petitioner’s delay was the product of good faith pursuit of viable legal claims rather than a frivolous attempt to prolong removal[115]—reviewing courts ordered a bond hearing in more than three quarters of the cases in which petitioner delay was found to be in good faith. Not all courts that considered petitioner delay, however, probed the reasons for the delay, with some counting petitioner-initiated slowdowns against the detainee regardless of the reason for that postponement (e.g., pursuit of viable legal claims or a bad faith attempt to avoid removal).[116] Because of that inconsistency, there is no data on how often, if ever, petitioner-caused delay actually reflects attempts by detainees to prolong a meritless immigration case.

Even though statistics on the reasons for petitioner delay are not readily available, anecdotal evidence suggests that it is often the product of the legitimate pursuit of legal entitlements rather than bad faith. Judge Carol King, an attorney with more than three decades of experience in immigration court, including twenty-one years as an IJ in San Francisco, explained in a declaration that “delays in adjudicating asylum claims are inevitable.”[117] Judge King noted that it is “typical” for IJs to grant multiple continuances in any given asylum case for good cause (for instance, to allow the applicant time to gather evidence or engage an attorney).[118] She went on to explain that it is more difficult for detained asylum seekers to collect the evidence necessary to support their cases than it is for their free peers due to limited access to telephones, the Internet, and translators in detention.[119] Immigration practitioners echoed Judge King’s sentiment, reporting that it was difficult for them to communicate with their detained clients.[120] In evaluating petitioner delay, judges should be mindful that there are many legitimate reasons why a detained individual would genuinely need more time to prepare their immigration case, and that holding an individual in detention only amplifies the challenge of preparing for court.

The factor of petitioner delay explains the disparate outcomes in Bayona-Castillo and Malcolm A. H. While the petitioners in both cases had the same immigration status, were detained under the same immigration statute for similar lengths of time, and were heard by the same federal judge,[121] delay was found in one case but not the other. In Bayona-Castillo, the district court attributed more than five months of the petitioner’s detention to his own unreadiness for litigation.[122] By contrast, in Malcolm, the district court found “no evidence which suggests . . . that Petitioner is challenging his removal in bad faith.”[123] Haynes’ petition was granted, and Bayona-Castillo’s was denied. Therefore, petitioner delay is not only a factor in the reasonableness analysis, but also a weighty factor that can be outcome determinative.

4. Lengthy Adjudication Times Exacerbate Due Process Violations

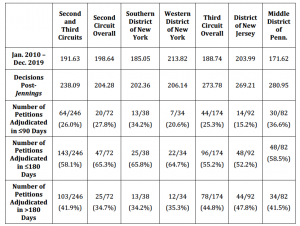

The time that it takes district judges to rule on the habeas petitions of immigrant detainees is long and getting longer. Table 3 shows that judges took an average of 191.63 days (nearly 6.5 months) to rule on the habeas petitions before them. Even in the most efficient district studied, the Middle District of Pennsylvania, judges took an average of 171.62 days (5.7 months) to issue their opinions. Alarmingly, the data also reveals that significant percentages of cases in every district studied took more than six months to adjudicate. Overall, nearly 42% of cases were not decided within six months (180 days) of filing. A stunning twenty-six cases did not have a decision a full year after their filing.[124] Lengthy adjudication delays persisted even when only considering recent cases. In fact, decisions were issued even more slowly after Jennings was decided in February 2018. The average post-Jennings adjudication took 238.09 days (7.9 months), an increase of more than a month from the overall average.

Table 3. Length of Adjudication (Days)[125]

On the flip side, the data also shows that it is possible to rule on an immigrant detainee’s habeas petition quickly. For instance, District Judge Analisa Torres of the Southern District of New York granted § 1226(c) detainee Marielle Fortune’s habeas petition only twenty-nine days after it was filed in a fully reasoned, six-page opinion.[126] Eight other cases in the sample were also decided after less than a month of consideration.[127] Table 3 shows that one out of every four habeas petitions was decided within three months of filing. The three-month decision rate was even better in some districts; Table 3 reveals that the Middle District of Pennsylvania and the Southern District of New York each addressed one in three petitions within that timeframe. While a judge’s ability to rule on habeas petitions efficiently varies based on their docket load and the complexity of the petitions before them, these cases show that efficiency is achievable.

Each month that a habeas petition is pending is significant given that most courts of appeals that have considered the question agree that prolonged detention is constitutionally suspect.[128] It is also important to note that § 1225(b)(1) and § 1226(c) detainees are not released immediately when their habeas petitions are granted. District judges typically order an IJ to hold a bond hearing for the detainee within twenty days of the habeas decision, which adds to the amount of time that the petitioner is detained in violation of due process.[129] Furthermore, noncitizens who are granted a bond hearing may ultimately be denied release at that hearing, condemning them to months and sometimes years of additional detention before their actual removal from the United States.

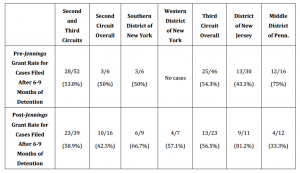

5. Jennings Did Not Change the Grant Rate Around the Six Month Detention Mark

Jennings did not change the constitutional analysis underlying individual due process claims to a bond hearing,[130] so district court outcomes should be consistent before and after the decision. There is a potential concern, however, that district courts interpreted Jennings’ rejection of the Second and Ninth Circuits’ bright-line rule granting bond hearings to immigrant detainees after six months of detention as an admonishment against finding constitutional violations around that mark. As Professor Theodore Becker famously observed, “when the Supreme Court sneezes, lesser courts jump.”[131] The reactions of trial judges to Supreme Court decisions may be influenced by the clarity (or lack thereof) of the high court’s command, the proximity of the judge to community pressures, and the judge’s personal preferences.[132] Because the Jennings Court did not instruct lower courts on how to conduct the due process analysis, individual judges animated by the spirit of that decision and/or community or individual concerns about immigration may now be less rights-protective than they were pre-Jennings. If habeas courts found violations around the six-month mark less frequently in the wake of Jennings than they did before the decision, there is a major fairness concern.

Table 4. Grant Rates for Petitions Filed After Approximately Six Months of Detention

Ten years of data provide key information on how courts across the country evaluate the habeas petitions of immigrant detainees. The data shows that most detainees filed their habeas petitions after being detained for six months to a year, and often it took just as long to get a decision from the habeas court. No length of detention predicted an order of a bond hearing; more than half of all denials occurred after more than a year of detention. Where the habeas court believed that the length of detention was due to the petitioner’s efforts to challenge their removability, it was much less likely that the petition would be granted, leading to disparate outcomes in otherwise similar cases.Table 4 shows, however, that the rate that district courts granted habeas petitions filed after six to eight months of detention was generally consistent before and after Jennings. The overall grant rate for those cases pre-Jennings was 53.8%, and actually rose to 58.9% for the period following that decision. Although the samples are small when broken down by district (ranging from six to forty-six cases), the grant rate rose in every district except the Middle District of Pennsylvania. The change in grant rate was modest in districts within the Second Circuit but rose by a noteworthy 37.9% in the District of New Jersey. The data allays any concern that district courts responded to Jennings’ rejection of a bright-line rule at six months by denying petitions filed in that time period. It is also consistent with the theory that length of detention is not the determinative factor in the due process analysis, and that other factors, including delay by the petitioner, are actually driving outcomes.

III. A Better Approach to Reasonableness

The Supreme Court could end this conversation definitively by ruling on the merits of the constitutional question and clarifying for affected individuals, lower courts, and advocates when due process requires bond hearings for immigrant detainees.[133] Although Jennings invalidated the bright-line rule approach as a matter of statutory interpretation,[134] the Supreme Court or courts of appeals[135] could still establish a bright-line rule as a constitutional holding, granting all § 1225(b) and § 1226(c) detainees bond hearings after a certain length of detention. This would be the most rights-protective and administrable solution because it would not require each detainee to file a habeas petition to vindicate his or her constitutional rights or subject detainees to unconstitutional detention. It would, however, guarantee bond hearings for all long-term detainees and clarify the legal duties of implementing agencies. A constitutional bright-line rule would also follow naturally from the Court’s holding in Zadvydas, which ordered bond hearings for all § 1231(a)(6) detainees after six months of detention.[136] Alternatively, the Court could rule that individualized reasonableness tests are constitutionally mandated, clarifying for lower courts which factors should be considered in the due process analysis and how to weigh them.[137] So long as lower courts continue to favor reasonableness tests, however, they should reform these tests to be more equitable and efficient.

This Part proposes two reforms that respond to the problems illuminated by Part II. First, federal courts should not consider delay by the petitioner in the reasonableness analysis, reserving that consideration for the bond hearing in immigration court. Second, courts should establish a rebuttable presumption that detention violates constitutional due process after no more than six months. Both modifications simplify the task of district courts, potentially shortening adjudication times significantly. They are also responsive to the weight that district courts currently give to various factors in the reasonableness analysis, shifting the focus from petitioners’ litigation choices to the length of their detention without process. Moving to an easily administrable, nationwide test will lead to more consistent outcomes among similar cases and make it more likely that individuals detained for prolonged periods will be afforded an opportunity to fight for their liberty.

A. Eliminate Factors that Speak to Bond Eligibility from the Constitutional Due Process Analysis

Federal courts should not consider factors that speak to bond eligibility when assessing the reasonableness of the continued executive detention of noncitizens. Instead, the analysis should focus on factors within the government’s control, like the length, conditions, and likely duration of detention. Because petitioner delay speaks to flight risk rather than whether detention serves the government’s purpose in effectuating a noncitizen’s removal, it is better evaluated at a bond hearing by an IJ than a federal judge in a district court habeas proceeding.

During bond hearings in immigration court, an IJ determines whether, if released, the detainee (1) is a danger to the community, (2) is a threat to national security, or (3) poses a risk of absconding instead of appearing at their future legal proceedings.[138] If the detainee is found to be dangerous, the IJ may deny bond entirely and order continued detention.[139] Absent a finding of dangerousness, the IJ determines what conditions of release (financial or otherwise) would mitigate any risk of flight.[140] At such bond hearings, the detainee normally bears the burden of proof.[141] However, when a habeas court orders an immigration court bond hearing based on a finding that a detainee’s prolonged detention violates due process, it routinely shifts the burden of proof to the government.[142]

IJs consider a number of factors in making bond eligibility determinations. In 2006, the Board of Immigration Appeals listed several factors that IJs may consider:

(1) whether the alien has a fixed address in the United States; (2) the alien’s length of residence in the United States; (3) the alien’s family ties in the United States, and whether they may entitle the alien to reside permanently in the United States in the future; (4) the alien’s employment history; (5) the alien’s record of appearance in court; (6) the alien’s criminal record, including the extensiveness of criminal activity, the recency of such activity, and the seriousness of the offenses; (7) the alien’s history of immigration violations; (8) any attempts by the alien to flee prosecution or otherwise escape from authorities; and (9) the alien’s manner of entry to the United States.[143]

Some of these factors speak to flight risk and others are proxies for dangerousness.[144] For instance, an individual’s criminal record may speak to their dangerousness, while community ties and historical attendance in court informs their risk of flight. Consideration of the factors listed in In re Guerra is neither required nor comprehensive; IJs have “broad discretion” in determining what factors to consider and how much weight to give each factor.[145]

It is more consistent with the purpose and framework of bond hearings to consider delay by the petitioner along with these factors at the bond hearing stage rather than during federal court adjudication of habeas petitions. Dilatory tactics by a petitioner are relevant to the flight risk inquiry because they suggest that the petitioner may be unwilling to accept an adverse outcome in their underlying immigration case. The case of Daniel A. v. Decker is illustrative.[146] In that case, the district court denied Haitian § 1226(c) detainee Daniel A.’s claimed right to a bond hearing, in relevant part because it was “Petitioner himself . . . wh[o] has prevented forward movement in [his] removal proceedings.”[147] Daniel A. had previously been released on bond after benefitting from a hearing under Lora, then failed to show up at his immigration court appointments and lost touch with his counsel.[148] The reviewing court attributed the government’s inability to move forward with his immigration case to this “disappearing act.”[149] While Daniel A.’s previous actions speak to the possibility that he would abscond again if released a second time, they had nothing to do with the length of his present detention (more than seven months), the conditions of his confinement, or other factors more directly related to procedural due process. The factor of petitioner delay speaks more to flight risk than due process, so is appropriately considered at a bond hearing, where the IJ can evaluate it in conjunction with all of the other facts that speak to a petitioner’s eligibility for bond.

There are also strong policy reasons for considering delay by the petitioner at the bond hearing in immigration court rather than in due process habeas proceedings. First, this approach conserves judicial resources by preventing the same issue from being relitigated in both proceedings and respects the divergent institutional competencies of federal and immigration courts. As the First Circuit recently recognized, “measuring reasonableness . . . requires a different inquiry than the flight-and-safety-risk evaluation conducted in an individualized bond hearing.”[150] Because any allegation that a petitioner purposefully delayed his immigration proceedings in order to game the system speaks to flight risk, such actions would likely be considered at the bond hearing regardless of whether they are considered in federal court first.[151] Congress could have vested the authority to hear immigration cases in the first instance in federal courts, but instead chose to create immigration courts in the executive branch, recognizing the value of the expertise offered by specialized bodies.[152] IJs hear asylum and withholding of removal claims regularly, so are better able to ascertain which of petitioners’ legal arguments and appeals are legitimate and which are merely delay tactics.

Additionally, this change would avoid penalizing noncitizens for pursuing their legal claims to withholding of removal or lawful status within the United States. Detention in prison-like conditions puts noncitizens in a terrible position: choosing between accepting deportation to the country from which they fled or pursuing lawful status in the United States while incarcerated. Though not detained for any crime, immigrant detainees are often incarcerated in criminal detention facilities designed for punitive detention.[153] As the Third Circuit has made clear, “merely calling a confinement ‘civil detention’ does not, of itself, meaningfully differentiate it from penal measures.”[154] The choice between tolerating detention and abdicating legal claims is even more impossible for noncitizens who are financially responsible for family members or who have health conditions that cannot be treated adequately in detention. Furthermore, those who choose to defend their case from prison face an uphill battle in finding adequate counsel and collecting evidence.[155] All noncitizens physically present in the United States have a right to apply for asylum.[156] Imposing this difficult choice on would-be asylees risks abrogating that right. Both the Second and Third Circuits have recognized the wrongfulness of punishing individuals for pursuing their statutory rights,[157] yet the tests currently employed in both circuits do just that.

Opponents of this reform may rightly point out that it is odd for habeas courts to turn a blind eye to certain factors when conducting a flexible reasonableness analysis meant to be tailored to the individual circumstances of each petitioner’s situation. However, this approach does not tolerate any factor being ignored completely—it merely divides the factors into two distinct inquiries based on institutional competency and the divergent goals of the habeas and bond analyses. While it is admittedly lopsided to consider government delay but not petitioner delay at the habeas stage, holding the government to a higher standard when it detains an individual is consistent with the fundamental constitutional value that “liberty is the norm, and detention prior to trial or without trial is the carefully limited exception.”[158]

Furthermore, this reform can be implemented easily and immediately because it does not require any action on the part of Congress, federal administrative agencies, or courts of appeals. The reasonableness tests currently operative around the country are judicial creations; no act of Congress was necessary to establish them, and no act of Congress is necessary to modify them. Because the current formulations of each of the reasonableness tests do not purport to be comprehensive and leave room for adaptation to individual circumstances,[159] no case needs to be overturned to remove petitioner delay from consideration. While a Supreme Court decision would ensure nationwide reform, district courts are free to modify their approaches to due process claims to bond hearings on their own in the meantime.

History shows that leadership in enacting this reform from even one district or circuit court could inspire others to follow suit. The cases establishing the current reasonableness tests draw from one another. Reid, the case establishing a reasonableness test in the First Circuit, directly cites the Sixth Circuit’s test.[160] Similarly, the 2016 Eleventh Circuit case, Sopo v. U.S. Attorney General, explicitly borrows some of its factors from the Sixth and Third Circuits.[161] After Lora was vacated, district courts within the Second Circuit looked to other courts around the country for inspiration in developing their own tests.[162] Individual judges have the legal authority to remove alleged petitioner delay from their due process analyses, and may spark widespread reform by doing so.

B. Streamline the Due Process Inquiry by Establishing a Nationwide Presumption of a Due Process Violation Before Six Months of Detention

Additionally, courts should presume that detention under § 1225(b)(1) and § 1226(c) is unreasonable by the time an individual has been detained for six months. Under this framework, after a set length of detention the government would bear the burden of establishing the constitutionality of continued incarceration. This solution has practical benefits and is easily implemented by district courts.

Applying a presumption of unconstitutionality after a set length of detention differs from the bright-line, six-month rule invalidated by the Supreme Court in Jennings. Although the effect of a new presumption would be largely the same as the rights enjoyed in the Second and Ninth Circuits under Lora and Robbins, it differs meaningfully because it would be established as a constitutional holding and not a constitutional avoidance reading of the detention statutes. Additionally, the bond hearing right granted by Lora and Robbins was automatic, meaning petitioners were guaranteed a hearing before an IJ after six months of detention.[163] Under a presumption of unconstitutionality, by contrast, the government would retain an opportunity to provide compelling reasons as to why there is no violation in an individual case (for example, because the detainee’s actual deportation is imminent). Although the Supreme Court remanded Jennings for consideration of the constitutional question, it hinted that consideration of individual circumstances may be required in the due process analysis,[164] an opportunity afforded by this approach.

Applying the procedural due process test from Mathews v. Eldridge, courts will likely find that such a presumption must kick in by the six-month mark. Under Mathews, courts weigh three factors to determine whether the Constitution requires the government to provide additional process: (1) the private interest, including the severity and length of the deprivation, (2) the risk of erroneous deprivation, including the value of additional safeguards, and (3) the public interest, including the fiscal and administrative burdens of additional process.[165] Applying the first factor, individuals have a “strong interest” in their physical freedom.[166] The liberty deprivation is particularly severe for detained individuals challenging their removability because detention severely impacts noncitizens’ ability to litigate their underlying immigration case.[167] There is also a high risk of erroneous deprivation. Because it typically takes habeas courts months to issue decisions on immigrant detainees’ habeas petitions,[168] individuals with meritorious cases are detained without process much longer than is constitutionally tolerable under the current system. Finally, while additional bond hearings would impose costs on the government, those costs would likely be offset because the government would no longer have to defend against habeas petitions in federal court. Immigration courts are already accustomed to providing bond hearings and each hearing can be as short as five to thirty minutes,[169] so the additional burden on the government would not be significant. The first two factors point strongly toward the need for additional safeguards for immigrant detainees, and the final factor does not compel a contrary result. These considerations are implicated immediately upon a detainee’s arrest and detention, so they likely require a presumptive right to a bond hearing long before the six-month mark and certainly by that point.

Courts should set this presumption at no later than six months of detention. In Zadvydas, the Supreme Court recognized that six months is a constitutionally significant length of detention without a bond hearing under at least one of the immigration detention statutes.[170] An outer limit of six months is also consistent with the understandings of the numerous courts of appeals which have warned that mandatory immigration detention for longer than half a year is constitutionally suspect.[171] District courts granted more than 55% of immigrant detainees’ habeas petitions filed between six and eight months of detention, so the judges closest to the facts agree that in the majority of cases, a constitutional violation has occurred by that time.[172] Courts at all levels recognize that by the time an individual has been detained for half a year, due process requires the government to explain why their continued incarceration is necessary.

Creating a presumptive constitutional violation around six months of detention would have practical benefits. First, it would better reflect when detainees actually file their habeas petitions. According to Figure 1, 36.9% of petitioners filed their habeas petitions immediately after the six-month mark (between seven and nine months of detention), and more than half filed between six months and one year of detention. A presumption is more predictable than current iterations of the test, reducing confusion among unrepresented detainees about the appropriate time to file. Had this rule existed during the period for which data was collected, the eighteen petitioners who filed before their detention reached six months could have waited for the precise point in time when the presumption kicked in, vastly increasing the odds that their petitions would be granted. A presumption would also lead to more consistent outcomes across cases and courts, a value championed by the Supreme Court in Zadvydas.[173] Finally, like the first proposal, the presumption would address the problem of lengthy adjudication expounded in Section II.D. Rather than undergoing complicated factual inquiries for each petition, district courts would only have to examine the factors that the government alleges override the presumption. This would be particularly efficient in pro se cases because it shifts the onus of adducing evidence to the government. Not only would a presumption protect important individual rights, it would also conserve judicial time and resources.

As with the first proposal, this solution could be initiated by federal district courts alone. None of the reasonableness tests employed by the courts of appeals explicitly foreclosed the possibility of a violation at or before the six-month mark, so district courts could begin implementing the presumption immediately.[174] Because the Third and Eleventh Circuits in Chavez-Alvarez and Sopo previously suggested that in some cases due process violations may not occur until after the six-month mark,[175] they should revisit those cases to clearly enact the presumption. The main challenge to implementing this reform is likely district court reticence to instate a rule that operates similarly to the rule recently invalidated in Jennings. But as previously explained, a presumptive violation is meaningfully different from an automatic right, and Section II.E demonstrates that, in practice, district courts have not shied from granting petitions filed around the six-month mark post-Jennings.

The two reforms proposed by this Part recognize that as long as courts use fact-specific reasonableness tests to determine whether the Constitution requires a bond hearing for immigrant detainees, those tests should be efficient, consistent across courts, and responsive to the relative competencies of federal and immigration courts.

The renowned “world-wide welcome” emblazed on the Statue of Liberty invites the tired, the poor, and the “huddled masses yearning to breathe free” to New York’s shores.[176] But once here, many immigrants seeking freedom are welcomed instead with jail cells. Because the Supreme Court declined to clarify when due process requires a bond hearing for immigrant detainees, the right is afforded inconsistently across cases and courts, resulting in years long detention in punitive conditions for many. By instating a presumption of unconstitutionality after a period of prolonged detention and postponing consideration of petitioner delay until the bond hearing before an IJ, nearly all noncitizens subject to lengthy detention would be afforded their day in court.

These reforms are just the beginning of the solution, however. Even if an immigrant detainee’s habeas petition results in a federal judge ordering a bond hearing, the chances of that detainee actually being released on bond are slim. Immigrant detainees represented by counsel are 3.5 times more likely than their unrepresented peers to be granted bond.[177] Only 42.9% of the habeas petitions studied in this Note were filed with the benefit of counsel, and this number is likely higher than the nationwide statistic because it includes individuals detained in New York State, which has guaranteed counsel to individuals facing deportation since 2018.[178] Section 1226(c) detainees, who by definition have criminal histories, are significantly more likely to be denied bond than individuals detained under other statutes.[179]

Detainees who are granted bond notwithstanding these hurdles may still be denied freedom due to their inability to pay the amount ordered by the court.[180] Immigration courts are not required to consider a detainee’s financial circumstances when setting bond,[181] and bonds are commonly set at tens of thousands of dollars.[182] Unlike individuals held in the criminal system, immigrant detainees do not have the option of purchasing their release at a discounted rate through a secured bond.[183] If liberty is truly to be the norm, due process demands more for immigrant detainees.

- United States v. Salerno, 481 U.S. 739, 755 (1987). ↑

- As of May 2019, 52,398 immigrants were detained by U.S. Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE). Hamed Aleaziz, More Than 52,000 People Are Now Being Detained by ICE, an Apparent All-Time High, Buzzfeed News (May 20, 2019), https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/hamedaleaziz/ice-detention-record-immigrants-border [https://perma.cc/XW28-2LU9]. ↑

- Section 33 of the Judiciary Act of 1789 included “an absolute right to bail in non-capital federal criminal cases,” and many early state constitutions included that same right. Timothy R. Schnacke et al., Pretrial Just. Inst., The History of Bail and Pretrial Release 4–5 (2010), available at https://b.3cdn.net/crjustice/2b990da76de40361b6_

rzm6ii4zp.pdf [https://perma.cc/7L3N-WA2P]. The right to bail in most criminal cases endures to this day. See generally id. (tracing the history of bail and pretrial release in the United States). ↑ - See Zadvydas v. Davis, 533 U.S. 678, 690 (2001) (“The proceedings at issue here [for removal of noncitizens] are civil, not criminal, and we assume that they are nonpunitive in purpose and effect.”). ↑

- See, e.g., Chavez-Alvarez v. Warden, York Cnty. Prison, 783 F.3d 469, 479 (3d Cir. 2015) (noting that the petitioner, an immigrant detainee, was held in a county prison alongside individuals serving criminal sentences); see also Sarah N. Lynch & Kristina Cooke, Exclusive: U.S. Sending 1,600 Immigration Detainees to Federal Prisons, Reuters (June 7, 2018), https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-immigration-prisons-exclusive/

exclusive-u-s-immigration-authorities-sending-1600-detainees-to-federal-prisons-idUSKCN1J32W1 [https://perma.cc/D4Y5-CJEK] (describing ICE’s plan to transfer 1,600 immigrant detainees to five federal prisons). ↑ - See, e.g., Hechavarria v. Sessions, No. 15-CV-1058, 2018 WL 5776421, at *1 (W.D.N.Y. Nov. 2, 2018) (explaining that a noncitizen had been detained for more than five years while he challenged his order of removal in court); Farray v. Holder, No. 14-CV-915-JTC, 2015 WL 2194520, at *3, *7 (W.D.N.Y. May 11, 2015) (denying immigrant detainee’s claimed right to a bond hearing after over 30 months of detention). ↑

- Lora v. Shanahan, 804 F.3d 601, 606 (2d Cir. 2015) (“[W]e join the Ninth Circuit in holding that mandatory detention for longer than six months without a bond hearing affronts due process.” (citing Rodriguez v. Robbins, 715 F.3d 1127 (9th Cir. 2013))). ↑

- Jennings v. Rodriguez, 138 S. Ct. 830, 842 (2018) (“The Court of Appeals misapplied the canon [of constitutional avoidance] in this case because its interpretations of the three provisions at issue here are implausible.”). ↑

- Criminal Aliens in the United States, S. Rep. No. 104-48, at 24–26 (1995) (expressing concerns related to the Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs’ finding that “[noncitizens] who have received written notices to report for deportation often fail to appear for their actual deportation”). ↑

- 8 U.S.C. § 1225(b)(1)(B)(iii)(IV). ↑

- 8 U.S.C. § 1226(a). ↑

- 8 U.S.C. § 1226(c)(1)–(c)(1)(A) (“The Attorney General shall take into custody any alien who . . . is inadmissible by reason of having committed any offense covered in section 1182(a)(2) of this title . . . .”); see also 8 U.S.C. § 1182(a)(2) (listing the crimes that render noncitizens inadmissible). ↑

- 8 U.S.C. § 1231(a)(2). ↑

- See 8 U.S.C. § 1226(a)(2)(A) (giving the Attorney General discretion to release §1226(a) detainees on bond and to set bond “conditions”); see also 8 U.S.C. § 1231(a)(3) (describing how the Attorney General may conditionally release § 1231(a) detainees if they are not removed in the first 90 days of detention). ↑

- 8 U.S.C. § 1226(c)(2) (stating that § 1226(c) detainees can be released “only if” their release is “necessary” to assist with a criminal investigation or prosecution, along with other conjunctive requirements); 8 U.S.C. § 1225(b)(1)(B)(iii)(IV) (“Any [§ 1225(b)(1) detainees] shall be detained pending a final determination of credible fear of persecution and, if found not to have such a fear, until removed.”). ↑

- Between January 1, 2010 and December 31, 2019, district courts in the Second and Third Circuits ruled on 249 habeas petitions from § 1226(c) and § 1225(b)(1) detainees. Of those cases, 200 were brought by § 1226(c) detainees and 49 were brought by § 1225(b)(1) detainees. Fewer than 25 were brought by § 1226(a) and § 1231(a) detainees in the same timeframe, respectively. See infra Section II.A for more information on the data used in this study. ↑

- Hechavarria v. Sessions, No. 15-CV-1058, 2018 WL 5776421, at *1 (W.D.N.Y. Nov. 2, 2018). ↑

- Id. at *2. ↑

- Id. at *1. ↑

- Id. at *6–7. ↑

- Falodun v. Session [sic], No. 16:18-cv-06133-MAT, 2019 WL 6522855, at *1–2 (W.D.N.Y. Dec. 4, 2019) (stating that Mr. Falodun was first taken into immigration custody on August 10, 2015 and finding that his continued detention violated due process on December 4, 2019). ↑

- Id. at *2 (explaining that the Board of Immigration Appeals issued a rare, precedential decision in Mr. Falodun’s appeal to hold that, despite the Attorney General’s previous recognition of Mr. Falodun’s derivative citizenship in the United States, the Department of Justice had authority to declare him a noncitizen (citing Matter of Falodun, 27 I&N Dec. 52, 52 (B.I.A. 2017)). ↑

- 8 U.S.C. § 1226(a)(2)(B) (parole of § 1226(a) detainees); 8 C.F.R. § 235.3(c) (2017) (limited parole of § 1225(b)(1) detainees). § 1226(c) detainees are not eligible for parole. See supra note 15. ↑

- Exec. Order No. 13767, 82 Fed. Reg. 8793, 8796 (2017) (“The Secretary shall take appropriate action to ensure that parole authority . . . is exercised only on a case-by-case basis in accordance with the plain language of the statute, and in all circumstances only when an individual demonstrates urgent humanitarian reasons or a significant public benefit . . . .”). ↑

- Elizabeth Knowles, Detained Without Due Process: When Does It End?, 96 U. Det. Mercy L. Rev. 77, 96 (2018). ↑

- Id. at 93. ↑

- For the source of federal jurisdiction over habeas suits, see 28 U.S.C. § 2241(a) (“Writs of habeas corpus may be granted by the Supreme Court, . . . the district courts and any circuit judge . . . .”). Habeas relief is available to prisoners “in custody in violation of the Constitution or laws or treaties of the United States.” 28 U.S.C. § 2241(c)(3). ↑

- See, e.g., Pierre v. Doll, 350 F. Supp. 3d 327, 332–33 (M.D. Pa. 2018) (finding that petitioner’s two-year detention without a bond hearing was “prolonged” and “unreasonable” in violation of procedural due process and granting his habeas petition in part). ↑

- Id. at 333 (“[T]he Court will grant in part the petition for writ of habeas corpus insofar as it seeks an individualized bond hearing before an immigration judge.”). ↑

- Plyler v. Doe, 457 U.S. 202, 210 (1982) (“Whatever his status under the immigration laws, an alien is surely a ‘person’ in any ordinary sense of that term. Aliens, even aliens whose presence in this country is unlawful, have long been recognized as ‘persons’ guaranteed due process of law by the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments.”). ↑

- Zadvydas v. Davis, 533 U.S. 678, 683–84 (2001). ↑

- Id. at 690 (“[W]here detention’s goal [of deportation] is no longer practically attainable, detention no longer bear[s] [a] reasonable relation to the purpose for which the individual [was] committed . . . .” (internal quotations omitted)). ↑

- Id. at 699–700. ↑

- Id. at 701. ↑

- Id. at 702. ↑

- Demore v. Kim, 538 U.S. 510, 530–31 (2003). ↑

- Id. at 513. ↑

- Id. at 523. ↑

- Id. at 522. ↑

- Id. at 527. ↑

- Id. at 529. ↑

- Letter from Ian Heath Gershengorn, Acting Solic. Gen., to Scott S. Harris, Clerk of the Sup. Ct. (Aug. 26, 2016), https://lawprofessors.typepad.com/files/demore.pdf [https://perma.cc/DY4F-CJ9Y]. ↑

- Demore, 538 U.S. at 531. ↑

- Id. at 531. ↑

- Id. at 532 (Kennedy, J., concurring). ↑

- Id. ↑

- Jennings v. Rodriguez, 138 S. Ct. 830, 838–39 (2018). ↑

- Rodriguez v. Robbins, 804 F.3d 1060, 1089–90 (9th Cir. 2015). ↑

- Docket No. 15-1204, Sup. Ct., https://www.supremecourt.gov/docket/

docketfiles/html/public/15-1204.html [https://perma.cc/W74T-WR99]. ↑ - Letter from Scott S. Harris, Clerk of the Sup. Ct., to Noel J. Francisco, Solic. Gen., & Ahilan T. Arulantham, ACLU Found. of S. Cal. (Nov. 10, 2017), https://www.scotusblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Letter-in-No.-15-1204.pdf [https://perma.cc/3ZKF-5C2C]. ↑

- Jennings, 138 S. Ct. at 842 (“The Court of Appeals misapplied the canon [of constitutional avoidance] in this case because its interpretations of the three provisions at issue here are implausible.”). ↑

- Id. at 851. ↑

- Id. (“[The Ninth Circuit] should reexamine whether respondents can continue litigating their claims as a class. When the District Court certified the class . . . it had their statutory challenge primarily in mind. Now that we have resolved that challenge, however, new questions emerge.”). Subsequently, the Ninth Circuit ruled in a different case that class injunctions are available on constitutional grounds under the jurisdictional provision implicated in Jennings. Padilla v. ICE, 953 F.3d 1134, 1151 (9th Cir. 2020). ↑

- German Santos v. Warden Pike Cnty. Corr. Facility, 965 F.3d 203, 210 (3d Cir. 2020) (“[W]hen detention becomes unreasonable, the Due Process Clause demands a hearing.” (quoting Diop v. ICE/Homeland Sec., 656 F.3d 221, 233 (3d Cir. 2011))); Reid v. Donelan, 819 F.3d 486, 494 (1st Cir. 2016) (“The concept of a categorical, mandatory, and indeterminate detention raises severe constitutional concerns . . . .”); Sopo v. U.S. Att’y Gen., 825 F.3d 1199, 1214 (11th Cir. 2016) (“We too construe § 1226(c) to contain an implicit temporal limitation at which point the government must provide an individualized bond hearing to detained criminal aliens whose removal proceedings have become unreasonably prolonged.”); Lora v. Shanahan, 804 F.3d 601, 606 (2d Cir. 2015) (“[T]he indefinite detention of a non-citizen raise[s] serious constitutional concerns . . . .” (internal quotations omitted)); Rodriguez v. Robbins, 715 F.3d 1127, 1138 (9th Cir. 2013) (“[T]o avoid constitutional concerns, § 1226(c)’s mandatory language must be construed to contain an implicit reasonable time limitation, the application of which is subject to federal-court review.” (internal quotations omitted)); Ly v. Hansen, 351 F.3d 263, 269 (6th Cir. 2003) (“[T]he time of incarceration is limited by constitutional considerations . . . .”). But see Parra v. Parryman, 172 F.3d 954, 958 (7th Cir. 1999) (applying the Mathews v. Eldridge test to find § 1226(c) detention constitutional, at least where the detainee concedes their deportability). ↑

- Robbins, 715 F.3d at 1138; Lora, 804 F.3d at 606 (“[W]e join the Ninth Circuit in holding that mandatory detention for longer than six months without a bond hearing affronts due process.”). ↑

- Robbins, 715 F.3d at 1138; Lora, 804 F.3d at 613. ↑

- Jennings, 138 S. Ct. at 842 (“The canon of constitutional avoidance comes into play only when, after the application of ordinary textual analysis, the statute is found to be susceptible of more than one construction . . . . [N]either of the two limiting interpretations offered by respondents is plausible.” (internal quotations omitted)). ↑

- Lora v. Shanahan, 719 F. App’x 79, 80 (2d Cir. 2018) (dismissing the Second Circuit’s 2015 Lora decision as moot because the petitioner’s removal had been cancelled and he was thus no longer in immigration detention); Rodriguez v. Marin, 909 F.3d 252, 256 (9th Cir. 2018) (remanding to the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California). ↑

- Marin, 909 F.3d at 256 (“Like the Supreme Court, we do not vacate the permanent injunction pending the consideration of these vital constitutional issues. We have grave doubts that any statute that allows for arbitrary prolonged detention without any process is constitutional . . . .”). ↑

- German Santos v. Warden Pike Cnty. Corr. Facility, 965 F.3d 203, 208–09 (3d Cir. 2020); Reid v. Donelan, 819 F.3d 486, 495 (1st Cir. 2016); Sopo v. U.S. Att’y Gen., 825 F.3d 1199, 1215 (11th Cir. 2016); Ly v. Hansen, 351 F.3d 262, 272–73 (6th Cir. 2003). ↑

- German Santos, 965 F.3d at 208–10. ↑

- The Sixth Circuit found that its prior reading of § 1226(c) was foreclosed by Jennings. Hamama v. Adducci, 946 F.3d 875, 880 (6th Cir. 2020). Other courts of appeals have not yet clarified whether their reasonableness tests remain good law. ↑

- See Guerrero v. Decker, No. 19-CV-8092 (RA), 2019 WL 5683372, at *4 (S.D.N.Y. Nov. 1, 2019) (“Jennings, however, only addressed what limits were imposed on detention under § 1226(c) as a statutory matter, leaving open whether due process concerns might otherwise limit § 1226(c)’s scope.”). ↑

- Sajous v. Decker, No. 18-CV-2447 (AJN), 2018 WL 2357266 (S.D.N.Y. May 23, 2018). ↑

- Hemans v. Searls, 18-CV-1154, 2019 WL 955353 (W.D.N.Y. Feb. 27, 2019). ↑

- Gomez Herbert v. Decker, No. 19-CV-760 (JPO), 2020 WL 1434272, at *2 (S.D.N.Y. Apr. 1, 2019) (noting that the Sajous framework has been “overwhelmingly adopted” in the Southern District of New York); Sankara v. Barr, No. 19-CV-174, 2019 WL 1922069, at *6 (W.D.N.Y. Apr. 30, 2019) (applying Hemans). ↑

- Reid v. Donelan, 819 F.3d 486, 500–01 (1st Cir. 2016). ↑

- Sajous, 2018 WL 2357266, at *10–11. ↑

- Hemans, 2019 WL 955353, at *6. ↑

- German Santos v. Warden Pike Cnty. Corr. Facility, 985 F.3d 203, 211–12 (3d Cir. 2020). ↑

- Ly v. Hansen, 351 F.3d 262, 271–72 (6th Cir. 2003). ↑

- Sopo v. U.S. Att’y Gen., 825 F.3d 1199, 1217–18 (11th Cir. 2016). ↑

- German Santos, 985 F.3d at 210; Sajous, 2018 WL 2357266, at *10 (stating that length of detention is “[t]he first, and most important factor”); Hemans, 2019 WL 955353, at *6 (“First, and most important, courts consider the length of detention . . . .”). ↑

- Sopo, 825 F.3d at 1220. ↑

- See, e.g., Reid v. Donelan, 819 F.3d 486, 500 (1st Cir. 2016) (explaining that a court may consider “the period of the detention compared to the criminal sentence”). ↑

- Sopo, 825 F.3d at 1217 (“[l]ooking to the outer limit of reasonableness, we suggest that a criminal alien’s detention without a bond hearing may often become unreasonable by the one-year mark”); Lora v. Shanahan, 804 F.3d 601, 615 (2d Cir. 2015) (“Zadvydas and Demore, taken together, suggest that the preferred approach for avoiding due process concerns in this area is to establish a presumptively reasonable six-month period of detention.”); Chavez-Alvarez v. Warden York Cnty. Prison, 783 F.3d 469, 478 (3d Cir. 2015) (“beginning sometime after the six-month timeframe considered by Demore, and certainly by the time Chavez–Alvarez had been detained for one year, the burdens to Chavez–Alvarez’s liberties outweighed any justification for using presumptions to detain him without bond to further the goals of the statute”); Rodriguez v. Robbins, 715 F.3d 1127, 1144 (9th Cir. 2013) (“[O]ur case law . . . has suggested that after Demore, brief periods of mandatory immigration detention do not raise constitutional concerns, but prolonged detention—specifically longer than six months—does.”). ↑

- Demore v. Kim, 538 U.S. 510, 513 (2003). ↑